Modern transportation has made travel to most places in Korea, no matter how distant from Seoul, easy and comfortable. However, there are exceptions. One of these exceptions is Ulleung Island. Its distance from the mainland and the fickleness of the local weather often make any trip to the island one of delays and seasickness—but those who travel there say that it is well worth the discomforts.

Despite its remoteness, Ulleung Island has been transformed and modernized over the past couple of decades. This is likely due in large part to the tourism associated with the nearby Dokdo sovereignty issue. But what was Ulleung Island like a century ago?

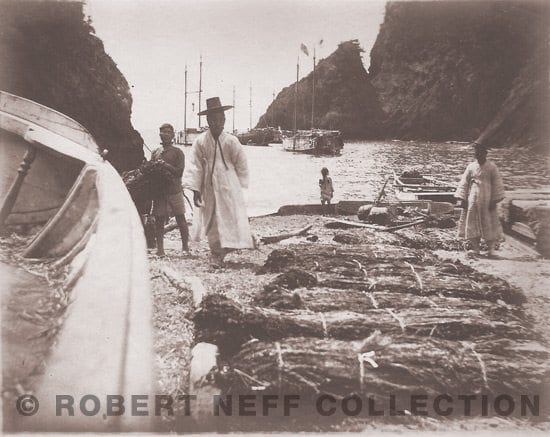

In the 1880s, the island was described as beautifully wooded with huge trees and a tall mountain that towered 4,000 feet above the sea. According to one visitor, it was relatively uninhabited except in the summer time, when Korean shipbuilders would arrive to cut timber for building ships.

But in 1883, the government equipped a number of Koreans with seed, livestock, provisions and weapons so that they could permanently settle upon the island. A small number of Japanese who had illegally dwelt and poached timber from the island were then deported back to Japan.

The timber was extremely valuable and, in 1884, became one of the first concessions Korea granted to a foreigner. The man was James F. Mitchell, an Englishman, and he was given the right to harvest timber and sell it in the foreign ports of Japan and China. Japanese newspapers of the time declared Mitchell the new king (pro tem) of the island. His reign, if one could call it that, ended rather quickly when it was discovered that the Korean government had granted the concession not only to him but also to an American and Japanese firm as well. Naturally enough, this caused some confusion and the concessions were basically nullified.

In 1898, a member of the Korean Customs Service visited the island and noted that it was populated by some 3,000 Koreans who were primarily shipbuilders and famers. He claimed, however, that Korean settlers from the mainland were coming in greater numbers because “life on the island is comparatively easy.” There were few taxes and the soil was so rich that two crops of wheat, barley, potatoes and beans could be grown each year. But the officer was surprised to discover no domestic animals in any form on the entire island, including dogs, pigs, horses and cattle. The only exception was a few chickens.

Apparently he was unaware that during the previous year, the island had been allegedly plagued with huge rats and birds that devastated the crops and caused great concern amongst the islanders.

But it wasn’t just rats and birds plaguing Ulleung residents. In 1897, a Korean named Bae Chung-jun arrived on the island claiming to have been granted the right to levy taxes and harvest and sell timber to the Japanese. He was extremely abusive and intimidated the islanders by attempting to murder some of them. Soon, a mob of islanders formed in resistance. They lynched Bae and hanged him from a tree in front of the government building before they dispersed.

There was also the matter of illegal Japanese immigrants—mostly from Oki Island. According to the Customs agent, there were some 200 Japanese men and women living on the island who were engaged in trade and lumbering. They imported kerosene, matches, cloth, and umbrellas and exported beans, barley, seaweed and, of course, poached timber. While some of the trade with the Japanese may have been beneficial to the islanders, there were also problems.

In April 1898, a group of Japanese men allegedly assaulted a Korean woman. In retaliation, a group of Korean men gathered and demanded retribution—but they were set upon by the Japanese, who were armed with swords and guns. A short fight ensued in which a Korean was wounded and the rest sent fleeing back to their village. The victorious Japanese then forced the Korean magistrate to grant them the right to harvest timber.

Just over ten years later, Korea ceased to be an independent country and became a part of the Japanese empire. No longer were the Japanese illegal immigrants but unwanted settlers.

Robert Neff has authored or co-authored several books including Korea Through Western Eyes and The Lives of Westerners in Joseon Korea. He currently writes a twice-weekly column for the Korea Times entitled “Did you know?” as well as a twice-monthly historical column for the Jeju Weekly.