Words by Samuel Murray

Shots by Samuel Murray, Matthew Merle Bula, Rodolfo Lesser, and Andy Mckilliam

R.O.K. Climbing: Vertical Endeavors in Korea

Why the hell am I doing this?

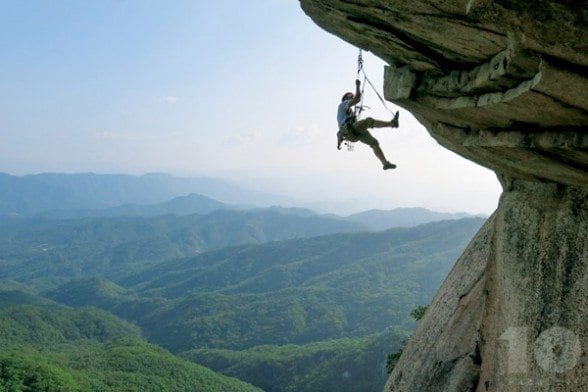

The question invariably passes through the psyche of every rock climber at some point, often when clinging desperately to some obscure dime-edge of granite, shaking, exhausted, sweating, frantically attempting to push fear and the thought of falling into the far recesses of the mind while fumbling to clip the rope through a carabiner. It’s a gripping moment, and the thought claws at the brain’s more gravity-compliant sensibilities with the threat of paralyzing panic. But the moment quickly passes, the clipping of the rope is successful, and safety from a fall is quickly reinstated. Exhale. Rock climbing in Korea is amazing with its beautiful landscape.

In many ways, rock climbing isn’t a rational pursuit. It goes against everything our brains and bodies are naturally inclined to do. Having both feet firmly planted on terra firma implies safety—grappling with various granite outcroppings forty meters off the deck does not. But climbing is only as scary or adrenaline-fueled as the climber wants it to be, provided that the climber is safe and knowledgeable.

Hollywood productions such as “The Eiger Sanction,” “Cliffhanger,” and “Vertical Limit” would have the common viewer under the impression that rock climbing is better reserved for neon-clad adventure addicts stimulating their own adrenal glands for more stoke juice. In reality, climbing is quite the opposite. Core strength and proper footwork quickly trump upper body build.

The unlikely equipment failures that seep through the storyline and drive the ill-fated plot of “Vertical Limit” are rare and are nearly always avoidable. “For those who see climbing as a dangerous or scary activity, but want to try it out, I always say that yes, indeed, it [can be scary or dangerous], but it doesn’t have to be,” says Peter Jensen-Choi, who owns and operates Seoul-based climbing guide service Sanirang Alpine Networks. “A person’s first few experiences out on the rock count for a lot, so it’s important for these experiences to be an especially safe, positive, friendly, and trouble-free introduction.”

Rock Climbing in Korea

For being such a small nation, South Korea boasts a respectable amount of rock. Climbers have discovered and developed nearly every inch of an exposed vertical face with the same fervent sense of urgency that helped the populace rise from post-war poverty to a state of economic prominence. Despite this, the country remains a relative unknown in the international climbing circuit. It lacks the dripping limestone overhangs and seaside white sand approaches of Thailand and Vietnam, the eternal sprawl of warped sandstone boulders of South Africa, and southern India’s granite outcroppings strewn between ancient Hindu temples.

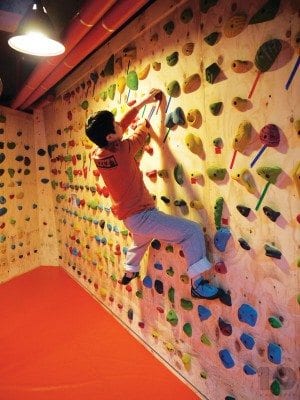

If Korea isn’t a preeminent international destination, however, then it certainly has a top-tier variety of climbing to offer residents. Rolling mountains cover roughly 80% of the country, exposing rock everywhere from the long granite lines of northern Gangwon’s Seoraksan National Park to seaside sport climbing on the southern tip of the peninsula. In between the abundance of natural rock is a myriad of steeply overhanging outdoor walls, impossibly small basement bouldering gyms, and indoor artificial ice walls. All of which have been quietly churning out world-class competition climbers and alpinists alike, including recent IFSC lead climbing world champion Jain Kim; 2013 UIAA overall lead ice climbing winner Hee Yong Park; and accomplished alpinist Chi Young Ahn. Who recently made the alpine-style first ascent of Pakistan’s Gasherbrum V with Nak Jong Seong.

Although climbing is beginning to take hold with younger generations in Korea, those who climb regularly outside typically hail from an older demographic, especially when compared to other niche sports such as surfing. “One thing that stood out straight away was the age diversity of the people dedicated to climbing,” says Madeleine Carlsson, a Swedish professor living in Seoul. “Before coming to Korea I never had any friends over 40, nor did I know anyone as mentally and physically strong as the older Korean climbers I go climbing with on a weekly basis.”

The group mentality that pervades much of Korean culture is also present in climbing. Large groups are common at outdoor climbing areas, and trips are typically done with entire climbing clubs or gyms. Korean climbers tend to focus heavily on repetition and training, which is especially present in the gym culture. “I pretty much spent my first two years with no foreign friends,” recalls American Sonia Knapp.

“Koreans train hard, and in the first year I went from 10b to sending my first 11d.” In a similar vein, Eimir McSwiggan, who had never climbed consistently before leaving Ireland to teach English in Korea in 2009. She attributes much of her ice climbing success to the regimented work ethic of Korean climbers. McSwiggan competed in the 2013 and 2014 Korean installments of the UIAA Ice Climbing World Cup (finishing 13th overall the latter year), and hopes to travel to compete in other legs of the circuit in 2015.

As with all communities rooted in expatriate life, the foreign climbing contingent in Korea draws from a constantly rotating pool of faces. Despite this (or perhaps because of it), the community remains tightly woven and inclusive. “It’s easy for a lot of people to get into climbing here because everyone is super supportive of beginners and everybody has an extra gear and is willing to take out newbies,” says Theresa Mowat, who learned to rock climb after coming to Korea in 2009, and has gone on to climb in China, India, Greece, South Africa, Turkey, and Thailand.

“When I was first getting into climbing I liked the sense of community. I would take a bus-train-bus-taxi to some random crag in the middle of nowhere with a bunch of people and go climbing and camping for the weekend. It was an adventure.”

People who were experienced climbers before moving to Korea share a similar sentiment. “I started climbing in Squamish, British Columbia,” says Chloe Sharpe, who has been teaching in Korea since 2012. “[BC] attracts climbers from all over the world, [and] the community is so large that I often found it difficult to find a solid crew of people to climb with. Korea welcomed me into its small community, and I found that there was a lot of support and encouragement from others, even from people I had just met.”

The accessibility of route information and the ease with which people organize climbing trips and find climbing partners in Korea has not always been as prevalent as it is today. Prior to the widespread use of social media, the foreign climbing population existed mostly in isolated pockets spread across the country. Limited English resources made it difficult to find partners, and the majority of expats climbed with their local Korean climbing gyms or clubs. “The expat climber scene was pretty scattered and small in comparison to today,” says Jake Preston, who has lived and taught in Korea since 2001. “Via the grapevine, we knew of a few expats here and there, but there were no Facebook, Twitter, or smartphones then. Hell, most of us didn’t even have a cell phone!”

In 2003 American Eric Busch came up with the idea of building a web portal for expat climbers in Korea. His experiences with the local Korean climbing community inspired the idea. “I had never climbed before I came to Korea in 1999,” Busch recalls. “When I first stepped into the Daejeon Climbing Center, the local Korean climbers immediately took me under their wing and showed me how to climb. I was blown away at their generosity and willingness to include me in their group.”

Motivated by his gym’s inclusiveness, Busch wanted to pay the favor forward. He designed an English web platform that groups climbing areas and routes based on region, calling it Korea on the Rocks (KOTR). After launching in 2004, the website quickly gained popularity and saw continuous updates from users. “It wasn’t so much a growth in the number of climbers as it was new connections between those climbers, which made the community seem larger,” says Busch. Within a few months, over a dozen climbing areas that he had never heard of had been added to the site.

Knapp was among the most active contributors to the KOTR website from early on: “I made it a point to search the Korean websites and find new areas, and through the website, I could find people who were willing to explore with me. I’d often try to find the places on Fridays so I could post them and take people there during the weekends.” Today KOTR contains access and route information for more than 300 Korean climbing areas and remains a primary English resource for regional climbing information on the peninsula.

KOTRI Korea on the Rocks Initiatives

Due to the inherent risk involved in the sport, climbing areas demand constant maintenance to ensure safety and help mitigate unnecessary dangers for those who climb there. Crags are seldom privately regulated, so the responsibility often falls upon the climbers themselves. Time, money, inexperience, and indifference, however, prevent many climbers from contributing to the upkeep of their local climbing areas. This is where groups such as Korea on the Rocks Initiatives (KOTRI), a nonprofit rebolting organization that voluntarily maintains and improves climbing areas throughout Korea, become essential.

KOTRI was founded in 2009 by American professor Bryan Hylenski, who has lived in Daegu since 2010. “When I first met the guys at KOTR, I was impressed with how a simple website had helped organize an entire community,” says Hylenski. “It allowed foreigners to be a part of something bigger than themselves, a community of climbers who took care of each other and had a good time doing it.” He saw an opportunity to complement and build upon the ongoing development and cleanup efforts of Korean climbing clubs. “If we started organizing initiatives to give back to the community and bring Korean climbers and foreign climbers together in joint projects, the community would start to develop a backbone based in service.”

The group’s first initiative took place at Yongseo Pokpo, a popular climbing locale in South Jeolla. Working with the local Korean club Gwangyang Climbers, volunteers replaced degraded bolts, restored trails, installed new climbing anchors, and established a recycling program for local restaurants and guesthouses. KOTRI members have returned to Yongseo Pokpo every year since to continue their efforts. “Our team, in the beginning, was small in size,” Hylenski says. “But because of their spirits and willingness to volunteer their time, our organization grew quickly.”

In addition to organizing and sponsoring around ten separate initiatives throughout the peninsula each year, the organization puts on the KOTRI Film Tour, which is held annually in late autumn; maintains the Community Assistance Fund, a trust fund set aside to assist injured climbers or families of deceased climbers; and sponsors the Community Development Project, a grant program that helps members who are pursuing climbing-related projects. Recent recipients of the CDP include Robin Kimmerling, who coordinated and funded a local bouldering festival in Busan, and Matthew Merle Bula, whose film “SLOW: A Climbing Season in Korea” premiered at the 2014 KOTRI Film Tour.

Why do people climb?

The obvious response is for the activity itself. Dynamic movement hundreds of meters up a rock monolith invokes sentiments of what one might be inclined to call divinity. The remaining component, however, is the people who climb and the inclusiveness of the community.

Drawing from the expat minority, the foreign climbing community in South Korea is small. But from that niche has grown a strong communal and self-sustaining group of climbers. “There’s so much energy and support from everyone that even a day out on twenty-meter routes can get you stoked,” says Sharpe. “And when you come down off your project there’s always someone at the bottom waiting to share some gimbap.”

“It isn’t the climbing itself that makes the climbing scene here unique,” agrees Canadian Les Timmermans. “There’s more aesthetic climbing in many other countries. But here it’s the people. It’s the camaraderie that remains even when the faces change. It’s the shared joy in doing something exciting together. It’s the pig head stuffed with cash [a common Korean pre-climbing season ritual] to keep us all safe for another year. It’s what we’ve got, and it’s good.”

- Check out koreaontherocks.com for a comprehensive listing of local climbing areas and gyms organized by province.

- To learn more about Korea on the Rocks Initiatives and how to become involved, visit kotri.org.

- To purchase CLIMB, an English guidebook authored by Ryou Dong-il and Jonn Jeanneret, visit kotri.org/climb.

- For a direct line into the climbing community, join Korea Climbing Calendar, Seoul Climbers, Daegu Climbers, or Busan Climbers on Facebook.

- Visit sanirang.net for more information on rock and ice climbing courses from Sanirang Alpine Networks.

If you enjoyed this article make sure to check out How to do Incheon to Busan by Bike

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]https://10mag.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Matthew-Merle-Bula.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]Matthew Merle Bula is a visual artist from Canada currently living in Busan. Most of the images that he makes have nothing to do with climbing.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]https://10mag.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Andy-Mckilliam-1.jpeg[/author_image] [author_info]Andy Mckilliam has been climbing, shooting, and searching all around Korea since 2009. He now lives in Australia doing research on consciousness, and still climbs and shoots photos when he can. His more recent work can be found at: tumblr.com/blog/andymckilliam.[/author_info] [/author]

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]https://10mag.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Rodolfo-Lesser.jpeg[/author_image] [author_info]Rodolfo Lesser was born Chilean but raised as a citizen of the world. A weekend warrior by heart, he likes to go on adventures climbing, skiing, or anything related to the great outdoors. You can find him climbing at a crag near Busan or enjoying some Korean BBQ. Follow him on Instagram at: @rodlesser.[/author_info] [/author]

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]https://10mag.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Austin-Vavrovics.jpeg[/author_image] [author_info]Austin Vavrovics is a Canadian English teacher currently living near Gunpo. He has previously worked as a commercial videographer and filmmaker. You can read about his experiences travelling, rock climbing, cycling, and scuba diving at: austinintheeast.wordpress.com.[/author_info] [/author]