We all know that students have it rough in Korea. They go to school early in the morning and then after school spend several additional hours in private learning institutes studying math and English. These institutes are everywhere now, but they haven’t always been.

In 1882—just prior to Korea opening to the West—Koreans who desired to learn English had to travel to Japan. But not everyone viewed the study of English as a good thing. When one young Korean scholar confided to his friend that he wanted to learn English so that he could study Western books, his friend scoffed at the notion, declaring it was instead more acceptable to learn the Japanese language because “the Japanese were less barbarous than Western nations.” Learning English would turn this young scholar into a barbarian. When the scholar insisted on learning English, his friend threatened to kill himself as he could not bear to think of his companion becoming a barbarian.

The first English language school established in Korea was in September 1883. The instructor was Thomas E. Hallifax, a 41-year-old Englishman who was somewhat a jack-of-all-trades. Prior to coming to Korea he had served as a sailor, telegraph operator and, for a period of four years, as a teacher in Tokyo. While many of his contemporaries—and for that matter, modern historians—viewed his efforts as lackluster at best, he did manage to instill enough interest in his students to inspire them to use their limited English.

In January 1884, Percival Lowell, an American residing in Korea, recalled that a small group of boys used to tap on his window in order to practice their English.

“The boys were proud of what little they had already learned, and took infinite delight in wishing me good morning in my native tongue. One of them, either more adventurous or more advanced than his fellows, next tried to put a few words together and then was summarily corrected by his more bashful friends, with that sudden temerity begotten in youth by the all-importance of the fact at issue—such corrections being, or course, oftener wrong than right.”

According to Lowell, “the boys were assiduous in their visits,” but were always polite. One boy proudly presented his new American friend with some paintings that he had done, eliciting Lowell to comment: “To be born a Korean is already to be born half an artist.”

In 1886, the Korean government established the Royal English School and hired three American teachers to instruct the sons of noblemen in not only English but also eleven other subjects including math, geography, medicine and natural sciences. Eventually the novelty of the learning experience waned and the students began to skip classes. Even the threats of punishment—both to them and their parents—could not deter the students from the pursuits of entertainment outside of their classrooms. The school eventually closed.

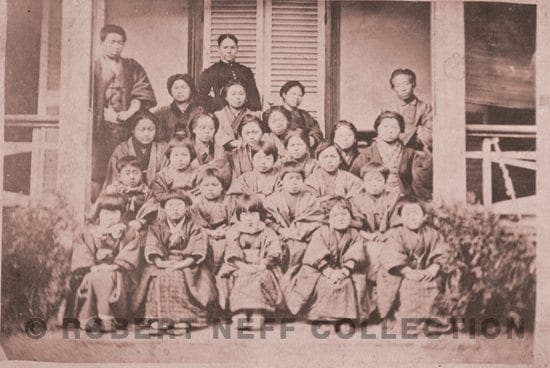

Missionaries also established schools. In 1886, Mary F. Scranton, an American, established Ehwa Hakdang (Pear Flower School), a school for girls. One early teacher recalled that it started out as more of a place where poor girls would be fed and clothed rather than a place of education. The school is now known as Ewha Womans University and is one of the most prestigious schools in Korea.

But not all English was learned in schools. Some of the Westerners employed by the Korean Customs Service moonlighted as English teachers—mainly to Japanese but also to the occasional Korean. It seems to have been fairly lucrative. Jonathon Hunt, an Englishman in Seoul, earned $20 a month teaching a couple of Japanese merchants.

English was also learned on streets and around the ports that foreign sailors and soldiers frequented. On Geomundo Island, a group of boys followed the British sailors around asking for tobacco in broken English. When their requests were denied, the Korean boys lashed out at the startled sailors in a “volley of British oaths”.