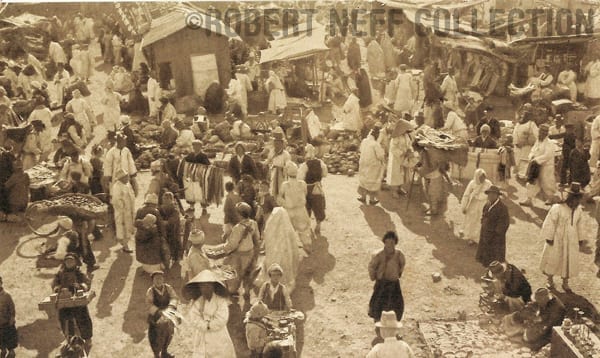

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, one of the most important events in village life was the five-day market. As there were few, if any shops, in the villages and small towns of the interior, people depended on these markets for the goods they could not they could not locally produce.

Pusang (itinerant peddlers) were responsible for bringing the goods to these markets. Isabella Bird Bishop, an elderly British woman who traveled extensively in Korea in the mid 1890s, described them as “mostly fine, strong, well-dressed men, either carrying their heavy packs themselves or employing porters or bulls for the purpose.”

They were not the only ones on the road – so, too, were the customers. People would come from miles around to buy provisions and goods needed for the following week.

Lascelle Meserve – a young woman who was at the American-owned Oriental Consolidated Mining Company (OCMC) in the early 1900s – wrote:

“Some came on foot, others astride tiny donkeys, their feet dangling to the ground. The small sturdy, vicious Korean horse figured prominently in these processions, saddled with a pack, and a native astride without stirrups. There was something biblical in the sight of these white-robed men with black horsehair hats straddling their miniature mounts. Bulls are also used as beast of burden. Occasionally a closed palanquin, perched at a perilous angle on a bull’s back and lurching with each movement of the beast, sheltered a Korean lady who must never been seen in public.”

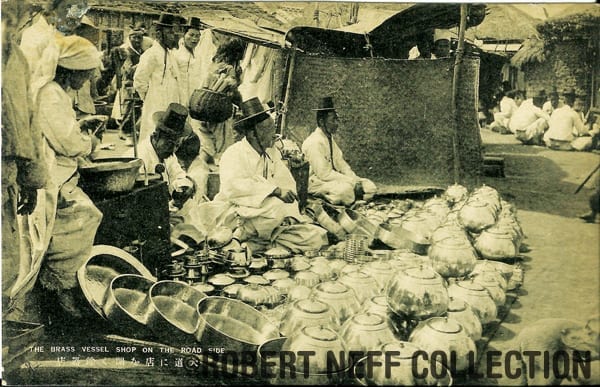

The market began early in the morning and was filled with a myriad of customers and merchandise. Common items, such as cooking pots, nails, brooms, vegetables, peanuts, paper and Korean silk were displayed on small tables or mats.

Luxury items, for those with the money, could also be found: dress shoes, makeup boxes with mirrors, tortoise-shell combs, buttons, and imported goods including Western and Japanese cloth and Japanese cigarettes with matches. Even the traditional long pipes – contraband items in Seoul at the time due to reforms in the mid-1890s – were openly sold.

Undoubtedly, the coops of live chickens and other fowl, piles of dead pheasants, “torn and hacked pieces of bull beef”, as well as other types of meat – including dog – were more-than-attractive to not only potential customs but also to the swarms of flies that plagued the markets in the summers.

American gold miner Paris Allen Lewis described the confusion and noise that reigned in the market in the early 1930s:

“The tinkling of the bells on the ponies and the deeper sounds of the cowbells on the oxen, mingle with the hoarse shouts of the barkers calling people to their wares. Yelling and squalling children and babies; barking dogs of which there seem to be thousands; the moo of the bulls and the whinnying of the ponies; the bells of the bicycles and the few, but loud horns of the autos. All these form a background or base for the shrill cries and shouting of the people arguing with the merchants over the price. It is almost some kind of symphony and sometimes seems to have a sort of rhythm to it.”

Of course, haggling often became animated and quarrels over the price or quality sometimes escalated to physical confrontations much to the enjoyment of the on-looking men and boys.

It was this threat of violence and the curiosity of the common people that required Western women to only attend these markets with a male escort – at least in the early 1900s.

Bertha Crawford, whose husband was a gold miner with the OCMC, recalled:

“Naturally we women enjoy going to market; but, as there are thousands of Koreans, Chinese and Japanese in the marketplace, many of whom have never seen a white woman, it is not thought best for us to go without a masculine protector, and who wants to go shopping with a man dogging one’s footsteps, a long staff in his hand to keep the inquisitive native at a proper distance?”

The bustle and noise weren’t the only characteristics of the market that attracted the attention of the Western visitors. In a letter to his mother, Lewis described the smells that permeated the market:

“Dried fish hanging in the sun; great strings of garlic that send out odiferous waves that almost overwhelm you as you pass by; cabbage and kimchi of doubtful age but certainly strong smelling; incense of all odors and descriptions; the smell of pigs that run loose in the streets; sweating ponies and oxen; stinking dogs; and through all of this the heavy odor of the sweat of hot, dirty people.”

While many Westerners cringed at the market’s reek, Lewis actually welcomed it; for he thought it helped “stamp the picture” of the market in his memory. As daylight waned the market began to empty. The merchants and shoppers were eager to get home before nightfall.

Darkness, especially in the early 1900s, was still ruled by tigers and wolves, and no one wanted to chance an encounter with these monarchs on a lonely stretch of road.

Those who were unable to leave in time spent the night in inns drinking and regaling one another with exaggerated boasts of their haggling skills or tales of their encounters with the dangers of the road.

Visages of these markets can still be seen in apartment complexes throughout Seoul. If you get a chance, go out and experience one.

They are much smaller than those of the past but they still provide a festive atmosphere of colors, noises and smells. And, if your haggling skills are good, you may end up with a great bargain and bragging rights.