In 1882, three courageous American officers became the first Westerners to step foot in Busan.

Words by Robert Neff, Pictures from the collection of Robert Neff

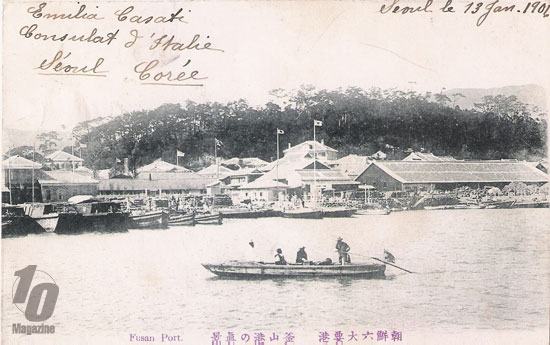

When the intrepid elderly British adventurer Isabella Bird Bishop visited Fusan (modern Busan) in January 1894, she declared, “It is not Korea but Japan which meets one on anchoring.” She was, of course, referring to the large population of Japanese that literally dominated the foreign settlement of that port, and, for the most part, the surrounding Korean community.

The Japanese had been conducting limited trade in that region since the fifteenth century, but it wasn’t until after the Korean-Japanese Treaty in 1876 that large numbers of Japanese began to settle in the region. By 1882, the Japanese settlement consisted of nearly 2,000 people living in Japanese-style homes, many of them brought over from Japan in sections. There were also a large Japanese consulate, a bank and a modern hospital, all built in the European style.

Foreigners, with the exception of the Japanese, were not allowed to visit Fusan until after the Treaty of Amity and Commerce between the United States and Korea was signed on May 22nd, 1882. Following the signing, the first Americans to visit Fusan were three naval officers: B. H. Buckingham, George C. Foulk and Walter McLean. The three men were returning to the United States through Russia and Europe and took advantage of the recent signing of the treaty to visit the port while bound for Vladivostok.

Aboard a Japanese steamship, they left Nagasaki, Japan, on June 6th and arrived at Fusan the following day. When a group of Koreans boarded the ship, the officers befriended them by speaking Japanese. Through their conversation, the officers learned that the Koreans were not averse to their going ashore and visiting their villages—provided, of course, that they had received permission from the Japanese authorities.

It was obvious that the Japanese were not going to grant them permission; their steamship tickets were clearly stamped with the words “Passengers other than Japanese not allowed to land at Fusan and Gensan [Wonsan] in Korea.” Determined to go ashore, the three naval officers tricked a young Japanese boatman into providing them with passage in his small boat.

Once on land, the Americans immediately proceeded out of the Japanese settlement of Fusan and headed towards the Korean walled city of Pusan. Although the officers never admitted it, surely they must have felt some apprehension as they left the relative safety of the Japanese community. Japanese newspapers in 1880 reported that Americans were so despised in Fusan “that even small children are disposed to show resentment at the sight of [Americans].”

A journal account from 1891 appears to corroborate this anti-American sentiment. An American missionary was disturbed to discover that Korean women and children ran away whenever he approached. “It is strange to find oneself regarded as an object of terror,” he lamented.

But on this visit in 1882, the Americans were mostly well treated. Foulk recalled that “a great crowd of Koreans collected about us, evincing much curiosity in examining our persons and clothing and asking questions, but were harmless and good natured.”

The only time they encountered any hostility was when they tried to enter the fortified residence of the local official: “[The] faces of the accompanying crowd for the first time showed alarm and anger, and as we were entirely dependent upon their good nature, we contented ourselves with a good view of the interior, easily obtained over the walls from a neighboring hill.”

Unlike the Japanese, the Koreans appeared “to live in great poverty.” The Koreans dwelt in houses of the “rudest description” and “numbers of naked children, with their bodies blackened by the sun, ran here and there, and smaller babies were carried in cloths slung over the hips of the women.”

They were somewhat surprised by the number of Korean women they encountered. According to Foulk, “it is commonly reported that Korean women are confined strictly indoors, and, therefore, rarely seen by visitors, or even by the natives themselves, out of their own homes beyond fixed hours.” Foulk concluded that this might hold true in other parts of Korea but not in the Fusan area where “Korean men treat women with much more courtesy and consideration than is common in other parts of the East.”

Foulk described the Koreans as “tall and well formed, and in general their personal appearance and manner were more likely to command the respect of foreigners than that of either the Japanese or Chinese in their original conditions.” He also made a controversial observation: “[Their] hair varied in color from black to light reddish-brown, suggesting, with the varying obliquity of the eyes, sometimes straight like those of Europeans, the intermixture of Caucasian and Mongolian races.”

Several times the officers tried to purchase goods from Koreans they encountered but were met with polite refusals. The only shops they could find were simple affairs—displays of burnished tobacco pipes and sandals in front of small buildings, and a few crude restaurants.

After their jaunt through the Korean community, the officers returned to the steamship where they undoubtedly received a well-deserved scolding from the ship’s captain. Early the following morning the ship departed for Vladivostock.

Foulk’s relationship with Korea did not end with his visit to Fusan, however. In 1883, he served as an interpreter for the Korean mission to the United States. He accompanied them when they returned to Korea, where he served as military attaché at the American legation and then as the chargé d’affaires.