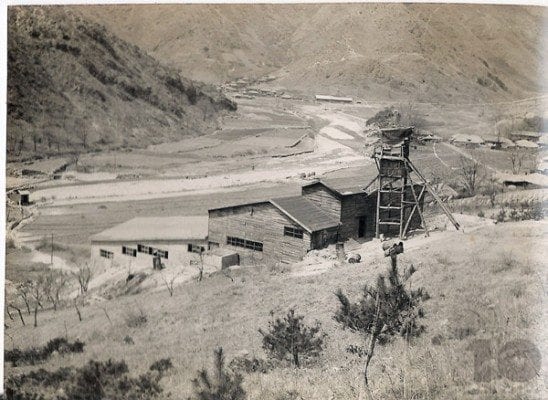

Many readers will probably be surprised to know that from the early 1960s through the early 1980s there was an American gold mining enterprise in Korea. Some won’t even knew there was even gold mining in South korea at all. It was known as the Korean Consolidated Mining Co. (KCMC), and received the first registration issued by the Korean Government to a foreign corporation under the Foreign Investment Encouragement Law.

The founder of the company was Richard S. Whitcom, (often referred to as ‘General” because he was a retired American general who served in Korea during the Korean War).

Korea has a long history of gold mining but it was mainly small placer mines. All of that changed, however, in the late 19th century when gold mining concessions were granted to foreigners – the largest being the American-owned Oriental Consolidated Mining Co. in northern Korea. Gold was said to be everywhere, even in the Han River.

The General was fond of saying, “It takes courage to make money; it takes money to mine” but money wasn’t the only thing he needed – he also needed trained personnel. There was no dearth of trained Korean gold miners but there were only a few experienced Western miners to act as supervisors at the various mining sites.

Thus, when Fred Dustin, an American teacher at Chungang University in Seoul who had also served in the military during the Korean War, asked the General for a job, he was promptly hired and sent to the Tongsan Mine in North Jeolla Province.

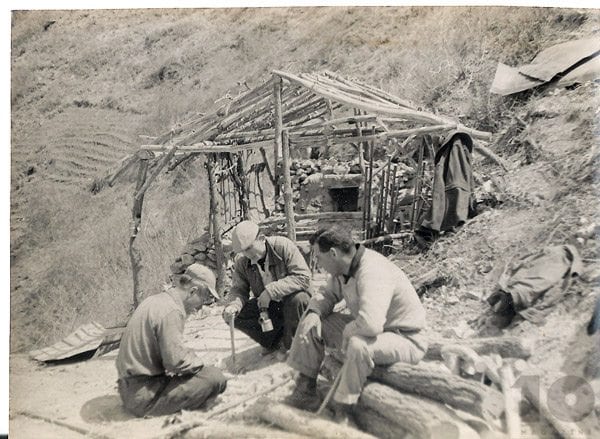

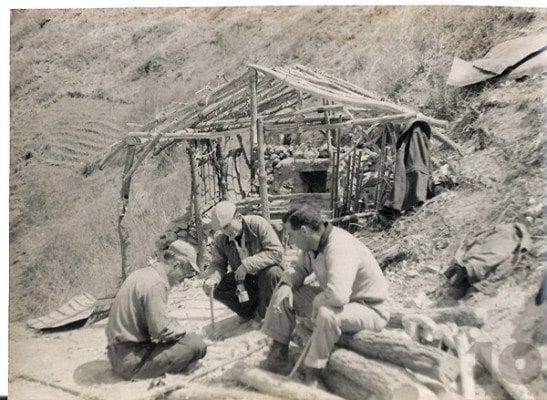

Life at the mine was far different from that in Seoul. Being in the mountains, it was very isolated. There was a small village of a few hundred people – at most – nearby but few of them could speak any English. Dustin’s constant companion was Sanyo (Mountain Girl), a black Labrador pup that he purchased for the princely sum of 300,000 hwan ($462).

Life at the mine was somewhat Spartan. When he first arrived, much of the mine’s infrastructure had not been built yet, including his sleeping quarters, and he was forced to seek accommodations in the home of one of the villagers until the following year when he added a bedroom to the mining office.

Dustin did much of his own cooking:

“Most often, breakfast was eggs fried or scrambled, bacon from the PX, baking soda biscuits or maybe pancakes and coffee: lunches were usually ramyon [sic]; supper would have been a pork roast or roast chicken; or maybe a can of pork and beans with toast,” he recalled and almost every week a pig was killed and butchered in the village and part of it was either given or sold to him. “Tubers like potatoes and carrots were always on hand and people from the village were always giving me the cabbage kimchee which they knew I battered and lightly fried.”

The Korean miners, most of them related to one another, earned 700 hwan ($2.13) for a full-day’s work (there was no overtime) and were paid in cash every two weeks. Most of them lived in the village and foraged for themselves

Sometimes they supplemented their diet with wild animals. In the fields near the mine, they hunted pheasants, ducks and grasshoppers (which were fried in cooking oil and were a favorite of Dustin’s). The stream also provided a bounty of food. During the summer and fall, crayfish were caught and used to make soups. Fish were also caught, but not by line and pole, but by dynamite.

For those with money and the lack of desire to cook for themselves, there were three small restaurants – including a Chinese one – that provided not only food but alcohol as well.

Mining is a thirsty occupation and the miners at Tongsan Mine were no exception. Dustin recalled that “beer was his mainstay” and there were only two beers available: “OB and Crown, but Crown was the favorite of most [people] in those days.” The beer was purchased from the Chinese restaurant and brought up to the mine office where, because there were no refrigerators, it was stored in the well. The well water was cool but undrinkable so the miners made due with water they boiled from the stream.

Mining is an inherently dangerous occupation and thus it is unsurprising that many of the miners were superstitious. Dustin recalled that the daily life of the Korean miners was “almost completely dictated by methods of appeasing the many spirits.” The miners depended upon the advice of a 72-year-old man named Yu (whose “father and his father’s father had lived in this village in the same house”) to console the Mountain Spirit whenever a new project was started at the mine. According to Dustin:

“Mr. Yu drank the first bowl of warm blood that gushed from the hog’s cut throat, the same hog whose head would dominate the place of honor on the ‘Kosa’ table surrounded by apples, pears, a dried fish or two, boiled port and wine.”

Despite the precautions – mortal and supernatural – there were accidents. One of the miners nearly lost his hand when he got it caught in a piece of machinery. Sanyo fell down a winze (shaft) and broke her legs, right shoulder and suffered internal injuries. She survived because of the kindness many Korean strangers showed to Dustin as he transported her to a vet nearly an hour’s distance away. Dustin was also a victim when some acid was splashed into his eye – either due to his own carelessness or the fickleness of the Mountain Spirit.

After he recovered, Dustin resigned his position with the plausible excuse that the work was too dangerous. But in truth, Dustin had simply “lost interest” in mining and sought a new adventure.

Ironically, now that fifty some years have passed, he fondly recalls that “it was the greatest experience of my life, those couple of years at Tongsan Mine, the dream of the General, the hands-on of actually digging gold out of a mountain, the unique experience (certainly now in retrospect) of living so ‘romantic’ a life as that of an actual gold miner.”

Time does heal all wounds and makes the past romantic.