In the summer of 1905, the world was a scary place for Korea. The Russo-Japanese War had recently ended but Korea was still occupied by Japanese troops and pressure from the Japanese government was increasing almost daily. Thus, when Emperor Gojong learned that Alice Roosevelt, the daughter of American President Theodore Roosevelt, was traveling with a diplomatic mission to Asia and would soon arrive in Korea, he began preparations to welcome her in a stately manner. It was perhaps the Emperor’s hope that he could favorably impress her and thus ensure her father’s aid with the Japanese.

One of the first things the Korean government did was to appoint Tommy Koen, an American engineer at the Korean palace, as the “Imperial Equerry and Master of Horse.” Koen, who prior to arriving in Korea had served as an oiler on a tramp steamer, seemed poorly qualified for such a position. Willard Straight, the American vice-consul, sarcastically declared that Koen had been chosen for the position because he had spent “his life on the bounding wave [and] knew all about horses or anything else that rocked.”

An imperial carriage drawn by a pair of grand black horses and four attendants in brilliant red uniforms were to be at Roosevelt’s disposal but a problem was soon discovered. The attendants were too big for their uniforms. On September 19th, she and her entourage arrived at Jemulpo and then proceeded to Seoul on a special train decorated with American, Korean and Japanese flags.

What became of the black carriage is unclear, but according to contemporary sources, a royal yellow chair was used to convey her through the streets of Seoul while the rest of her entourage was provided with other state chairs.

According to one observer, “Most of the houses in the city had been decorated with Korean and American flags, some of the latter lacking an occasional star or stripe, or showing somewhat of a variety of color, but all bearing evidence of a uniform desire to honor the nation’s guest.”

On September 20th, Roosevelt was received at Deoksu Palace and was treated with more consideration than [had] ever been shown to visiting royalty before. According to Willard Straight:

“At the first luncheon the Emperor brought Miss Roosevelt in on his arm and sat the same table with her. The Crown Prince also officiated at a plate and another Imperial figurehead, Yi Yong, was among those present. The rest of us were at smaller tables sandwiched in with prominent Korean officials, many of whom had by special order of the Emperor, got themselves into European clothes for the first time and who certainly did look, and from their appearance feel, like Hell. Their clothes were long and short and anything but what they should have been. It was a strange and wonderful sight to see Miss Roosevelt on the Emperor’s arm, or rather he on hers, as they came into the banqueting hall which looked more like a boarding house parlor than anything else.”

Despite Senator Francis G. Newman (Nevada) burning his mouth on a spoon that he had left too close to a piece of charcoal, the luncheon went quite well. The emperor took the opportunity to urge the senator to speak favorably to the American president concerning Korea’s situation in regards to Japan. The senator advised the Korean government to hire a lawyer to make a formal appeal citing the good office clause of the US-Korea treaty.

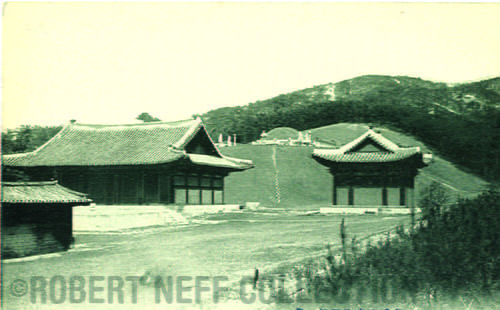

After several parties and excursions – including one to the tomb of Queen Min – the Roosevelt party left Seoul, by train, for Busan on September 29th. At the time, her trip appeared to have been very enjoyable but Willard Straight was quick to note in his correspondences that not all was as it seemed. He claimed that the Japanese had done everything they could to disrupt the visit.

The Japanese “were principally afraid of the effect that the visit would have on the Koreans. [The Koreans] are seeking for straws just now and the Roosevelt trip looked like a life preserver to their jaundiced imaginations. This the Japanese tried to get around by appearing to be doing the entertaining themselves.”

But there were other incidents that Straight failed to mention in his correspondence and had nothing to do with the Japanese. In 1909, Emma Kroebel wrote a book in which she described her life as the Mistress of Ceremonies for the Korean government. One incident she recalled was of Roosevelt’s appearance at Queen Min’s tomb.

She recalled that Roosevelt arrived at the party in a cloud of dust on horseback with a large escort of men. She was clad in a scarlet riding habit, beneath the lower extremities of which peeped tight-fitting red riding breeches stuck into glittering boots. In her hand, she brandished a riding whip; in her mouth was a cigar…everybody was bowing and scraping in the most approved Korean Court fashion, but the Rough Rider’s daughter seemed to think it all a joke.”

She apparently paid little attention to those around her but was fascinated with the stone statues that guarded the tomb. “Spying a stone elephant, which seemed particularly to strike her fancy, Alice hurtled off her horse and in a flash was astride the elephant, shouting to Mr. Longworth [her fiancé] to snapshot her. Our suite was paralyzed with horror and astonishment. Such a sacrilegious scene at so holy a spot was without parallel in Korean history. It required indeed ‘American ways’ to produce it.”

After a short chat with the American legation staff and bravely partaking of the champagne, she suddenly “gave orders of the saddling of her horse, and galloped away with her male escorts like a Buffalo Bill.” Many denied the event ever took place – including Alice’s father-in-law who declared Kroebel was “either drunk or crazy, or both.” The denials went on for some time but no one could or would provide the proof that was needed to finally put the matter to rest.

It wasn’t until the death of Willard Straight and the subsequent donation of his material to Cornell University that we can finally have an answer – a picture of Alice Roosevelt astride one of the statues at Queen Min’s tomb. Apparently Kroebel was neither drunk nor crazy.

All photos from the collection of Robert Neff.