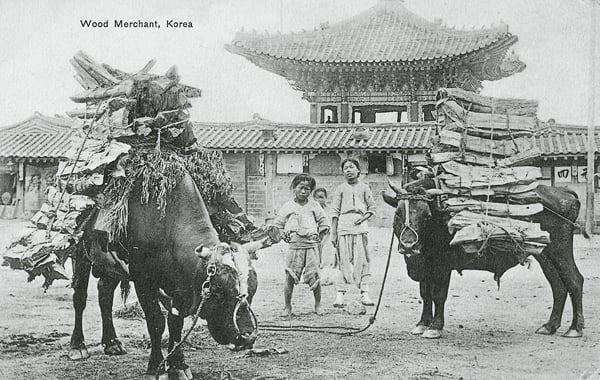

Photos from the collection of Robert Neff

One of the most valued animals in Joseon Korea was the Korean bull, which was used for transportation, food and leather. Westerners described these bulls as “noble” and “splendid beasts” that were not only “remarkably handsome” but very “tractable.”, thus the name of Korea’s noble cow. Although the Korean bull was a powerful creature, it was extremely gentle. By the use of the ring in a bull’s nose, even a small child could manage it.

Korea’s Noble cow’s history

Bulls were shod with iron shoes, like Korean ponies, and used to transport goods over the narrow and muddy paths that served as roads throughout the country. Unlike Korean ponies – notorious for their sheer orneriness – bulls and cows slowly and dutifully plodded through the streets with great loads of timber and brush.

But there was one thing that Korean cattle were not used for and that was milk.

Horace N. Allen, one of the first Americans to live in Korea, claimed that it was “remarkable that in Korea where are to be found such fine large cattle, there is no use made of milk, and this too in a land of such poverty that it would seem that all proper foods would be cherished as such. True they know the use of milk, since children, invalids and the aged use human milk, but the milking of cows is not practiced by the people.”

Koreans were not too pleased that their Western guests did not share their views on cow’s milk.

James Gale, a missionary, bought a cow so that he could provide his children with milk but soon found himself in hot water with his congregation. They were convinced that “it was a very un-Christian act to deprive the calf of milk God had provided for its nurture.” Gale tried to explain that farmers commonly milked cows in the United States with no ill effect upon the calves, but the Koreans were adamant with their views. Concerned that his position was in jeopardy, Gale gave in and his children were forced to “forego their fresh milk.”

Instead, many Koreans – as well as Westerners living in Korea – used canned condensed milk. At first, the introduction of canned milk was met with superstitious fear. In 1888, rumors circulated that the milk came from the breasts of Korean women which were cut off and sealed in the cans. This helped contribute to unrest that year that came to be known as the Baby Riots. Ironically, canned milk was prescribed by the foreign missionary physicians for Korean children. By the early twentieth century, canned milk was quite popular with the Koreans because of “its extreme sweetness – in a land devoid of sugar, except the sweet of honey, and that obtained from rice and similar grains.”

While many Koreans may have felt compassion for cattle and their calves, butchers were more concerned with profit than compassion.

Isabella Bird Bishop, an elderly English traveler, described one Korean butcher shop as follows.

“The Koreans cut the throat of the animal and insert a peg in the opening. Then the butcher takes a hatchet and beats the animal on the rump until it dies. The process takes about an hour, and the beast suffers agonies of terror and pain before it loses consciousness. Very little blood is lost during the operation; the beef is full of it, and its heavier weight in consequence is to the advantage of the vendor.”

Slaughter was not the only danger that awaited Korea’s noble cow. Every few years, rinderpest – a disease – decimated the cattle population throughout Korea, leading to large numbers of cattle hides exported to Japan and China. So devastating was this disease that in 1898 a Cattle Insurance Company was established by a favorite in the Korean court. The agents of this company went into the interior and compelled cattle owners to pay 20 cents a head for protection with the understanding that if the cow or ox should die from disease the company would pay the full price. It should come as no surprise that the company soon failed.

=============

If you want to know more about Korean beef, check this article on Kimcmarket.