Between the increasing regulations on hagwons and cuts in the number of middle and high school native English teachers, the last few years have seen significant changes in Korean education policy. The most controversial of these shifting policies, however, may have nothing to do with curriculum. The ongoing debate concerning whether or not to ban all corporal punishment in Korean schools dates back decades and reflects larger issues in Korean education.

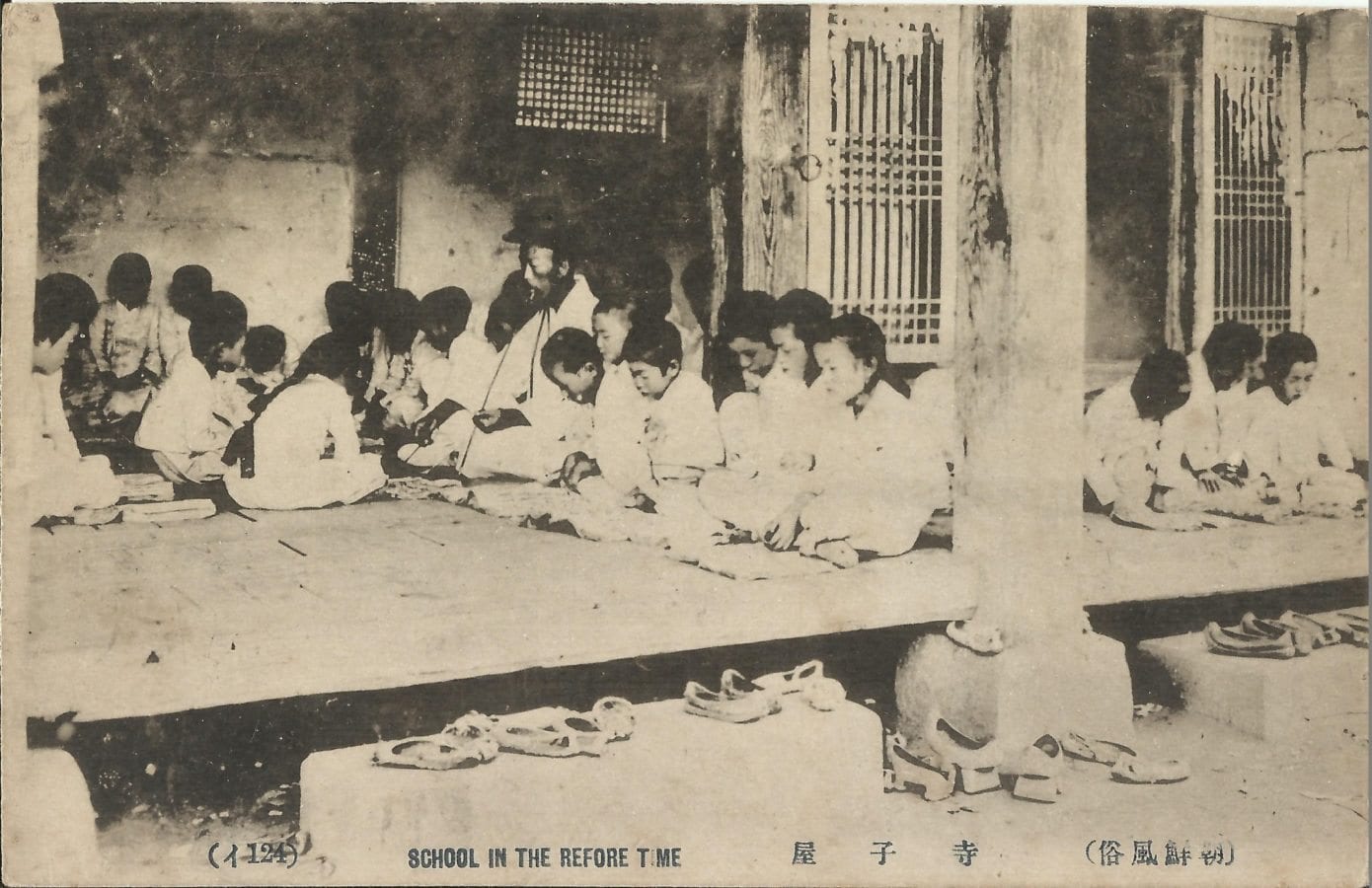

The use of corporal punishment in Korean schools began in the tenth century when Korea adopted Tang Dynasty China’s Confucianism-based education system emphasizing the teacher’s role as essential to learning material necessary for passing civil service exams, which the aristocratic class viewed as the primary benefit of education. Later, parent-funded village schools became the most popular form of education and striking students was common. By the early twentieth century, the village school model gave way to more Western style of education which was supplanted during Japanese colonization. According to Hanshin University Professor Soon-Won Kang, corporal punishment during the colonial period was especially harsh since students faced whipping if they expressed an interest in learning about Korean culture. Though Korea returned to a more Western-style education system following Japanese colonization, the resulting ideological commitment to capitalism lead to unprecedented competition among students.

Many, though not all, of the current advocates for continued use of corporal punishment were students during this period of competition. As the nation developed rapidly, it became imperative for teachers to maintain control of classes which often had up to 80 students. With few options, teachers relied on corporal punishment for discipline. Recalling the use of corporal punishment when they were students, many older teachers today hold no resentment toward their former instructors and say it was an effective way to keep the class in line. Having seen the potential usefulness of corporal punishment as students and lacking sufficient training on alternative disciplinary methods, they remain proponents of corporal punishment.

On January 3rd, 1999 an op-ed titled “Teachers, Cheer Up!” was published in the Korea Times. It was written by Tae-hwan Choi, then an English teacher at Kukje High School in Gwangju. The article addressed issues that had come up following the mid-1990s ban on so-called direct corporal punishment in Korean schools. Korean laws make a distinction between direct and indirect corporal punishment. Direct corporal punishment includes any type of hitting; indirect corporal punishment refers to all other methods of inflicting punitive bodily pain or stress on students—i.e. holding stress positions, exercise, etc. Though enforcement of the ban remains inconsistent, direct corporal punishment has technically been banned since the nineties. In the article, Choi lamented the decreasing respect for teachers, supposedly resulting from the ban.

In the intervening time between the ban and Choi’s article, there were multiple cases of students calling police in retaliation for even “mild” corporal punishment, a situation which at times hindered teachers’ ability to conduct class. Though the 18th Article of the 1997 Elementary and Secondary Education Act calls for a guarantee of students’ human rights, it states that head of schools may partake in disciplinary measures “deemed necessary for education.” As such, conflicts arose due to the subjective nature of the term “necessary.” Choi’s article showcased how varied Koreans’ interpretations were. Choi’s article primarily called for teachers to refrain from reacting emotionally to student misbehavior, but it implied that having the legal ability to engage in direct corporal punishment—whether supported by the students’ parents or not—is essential for teachers to be able to maintain their “dignity.”

For some younger Korean teachers today, Choi’s belief in an essential connection between direct corporal punishment and dignity may seem odd, but the use of some forms of corporal punishment does not. Even though older Korean teachers are more likely to support harsher punishments, the majority of Korean teachers have used some form of corporal punishment in the classroom. Sol Jeon is an English teacher in Kukje High School today – the same school where Choi taught – and he says “corporal punishment should be banned” but that “some of [his] co-teachers say corporal punishment has educational effects.” Because of this belief, corporal punishment is still widespread. A 2011 study published in a journal of the Korea Institute of Criminology and conducted by Dong-eui University Professor Cheol-hyeon Park found that 94.6 percent of interviewed high school students had experienced corporal punishment. A small interview-based study of Korean EFL teachers’ perspective on corporal punishment found that while some teachers prefer not to use corporal punishment, its short-term effectiveness make it attractive especially when dealing with large classes. The Korean Federation of Teachers’ Associations (KFTA) is one of the most vocal advocates for the continued legality of indirect corporal punishment.

In late August 2010, Seoul’s Education Superintendent No-hyun Kwak initiated a blanket ban on all forms of corporal punishment. In October of the same year, Gyeonggi Province followed suit by implementing its own ban and developing an incentives-based disciplinary system called the “Green Mileage” system, as well as providing guidance counselors and initiating the Family and Education Rights Support Group. KFTA opposed these changes. They criticized the Seoul Superintendent for creating a disciplinary vacuum in which teachers would not know how to discipline students due to the lack of comprehensive guidelines for alternative punishments. KFTA’s main criticism of the Gyeonggi Province ban was that the provided resources were untested and thus should not be implemented. Though these changes were swift, they were not unprovoked.

Just that past summer, the now-infamous Oh Jang-pung video became national news. In the surreptitiously filmed video, Mr. Oh, an elementary school teacher, beats a sixth-grader. Mr. Oh was notorious among students for his punishment and, in fact, Jang-pung was a nickname referring to a martial arts technique that the students gave him alluding to the severity of his punishments. The video sparked nation-wide outrage as media outlets continually discussed it. Though other such videos had existed before (and also since), the visibility of this video was unparalleled. The backlash created by the video likely inspired Seoul’s ban since Kwak claimed “it brought [him] great distress when [he] saw children go on as if nothing happened when cases like ‘Oh Jang-pung’ broke out.”

The widespread visibility of the Oh Jang-pung video brought a debate that had been going on for decades into the limelight in a way that showcased other potential problems in Korean education. The insistence of groups like KFTA that corporal punishment remains an important tool for teachers helped to highlight how the issue of corporal punishment does not exist in isolation. Writing in the Korea Herald on June 22nd, 2011 KFTA international coordinator Un-soo Jung highlighted the difficulties faced by teachers in disciplining students:

“In Korea we have about ten more students in a class on average than other OECD nations [.] We need effective guidance methods to protect the educational rights of the students. If we had about twenty students in one classroom it would be much easier to control the class and to approach and educate each student individually. So if the government or the provincial education offices really want to ban all corporal punishment, they should spend money on employing enough teachers to reach the classroom numbers of the rest of the OECD[.]”

In surveys, Korean teachers have identified two primary reasons for using corporal punishment even though it is not their preferred disciplinary method: (1) excessively large class sizes and (2) pressure to cover large amounts of material for testing purposes in limited time. Though teachers claim they prefer not to use corporal punishment, the in-classroom reality is that most think it is occasionally necessary—even younger teachers. In 2011—mere months after the Oh Jang-pung incident, more than 1,400 student teachers were surveyed on their views on corporal punishment and more than 60% opposed a ban. Interestingly, student teachers preparing to be secondary school teachers were slightly more likely to support corporal punishment than those preparing to be primary school teachers, perhaps the result of the larger class sizes and increased testing requirements in secondary schools. It is important to note that there have been significant changes to the public’s perception of corporal punishment. According to Jeon, when he was a student “people usually thought that if a student got corporal punishment, he usually deserved it,” while today corporal punishment has a “negative image.” The same survey also showed that corporal punishment is losing support among parents and students.

Despite support from parents, the bans on all corporal punishment were revised only months later. In Gyeonggi Province, attempts to admonish a teacher for making students do punitive push-ups resulted in KFTA opposition. Seeking compromise between supporters and opponents of corporal punishment, the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology changed Seoul’s policy from banning all corporal punishment to banning only direct corporal punishment. The Ministry’s revision was opposed not only by the Seoul Superintendent but also by the Gyeonggi, Gangwon and North Jeolla provincial education offices as well as the National Human Rights Commission, which have all been identified as having progressive views on corporal punishment.

Participants in the debate over how much, if any, corporal punishment should be legal are usually categorized as either traditionalists or progressives. Traditionalists are those that support the continued use of corporal punishment and other regulations on student behavior. Progressives seek a comprehensive change to Korean education policies which grants students greater freedoms they identify as human rights. While traditionalists tend to advocate for teachers’ rights, progressives are concerned not only with banning both forms of corporal punishment—since indirect corporal punishment is seen as degrading—but with increasing students’ rights in such ways as dropping uniform requirements and allowing students to keep their cellphones during school. These categories are permeable, however, as evidenced by Busan Superintendent Hea-kyung Lim. She publicly opposed Seoul’s ban, but has advocated for decreasing dress code requirements. Ultimately the debate over corporal punishment is more complicated than these labels suggest because the labels refer only to the ideological grounds for the groups’ positions with little insight into the consequences corporal punishment has on students.

Due to corporal punishment’s short-term effectiveness in correcting student behavior it is easy to understand its appeal for potentially overburdened teachers. Over the long-term, however, the usefulness of corporal punishment is questionable at best.

Ironically, studies have linked corporal punishment to increased misbehavior. The same Korea Institute of Criminology study that found nearly 95% of Korean high school students had experienced corporal punishment also found that corporal punishment lead to increased rebelliousness. Decades of research have shown that using corporal punishment prevents children from understanding why a behavior is wrong because they concentrate on the pain they feel rather than the lesson. According to a 2002 meta-data analysis of 88 studies conducted by Doctor Elizabeth Thompson Gershoff of Columbia University’s National Center for Children in Poverty, corporal punishment is associated with 11 effects–ten of which are negative. While the only positive association is with what the researchers term “immediate compliance,” the links to long-term aggression, misbehavior and anti-social tendencies imply that the children do not internationalize the lessons intended by the punishments but instead alter their behavior to avoid further pain.

Corporal punishment also negatively affects children psychologically. Though there is little definitive evidence that corporal punishment is a primary cause of depression, it has been shown to be a contributing factor under certain circumstances. Particularly with younger children, corporal punishment may lead to recurring nightmares and fear of authority figures. In the Korean context, with high-stake, high-pressure education systems, the adverse psychological effects of corporal punishment are important.

Korean teenagers are amongst the unhappiest in the world. While suicide rates have been dropping in developing countries, the suicide rate among Korean 15 to 24-year-olds has increased. According to a poll conducted by the Korea Health Promotion Foundation in February 2014, over half of Korean teenagers have had suicidal thoughts and about a third claim to be “very depressed.” Poll respondents claimed their depression stemmed largely from school-related pressure. Though information compiled by lawmaker Jae-jeung Bae of the New Politics Alliance for Democracy shows the main cause of student suicides 2010-2014 was family issues, school-related stresses including corporal punishment have been contributing factors in at least some cases. In 2009, two students committed suicides linked to corporal punishment in Gwangju. The first suicide was by a male high school student who hung himself after a teacher hit him with a rod over one hundred times. Weeks later, a female middle school student killed herself after being made to crouch repeatedly—a form of the more-widely accepted indirect corporal punishment. A similar case was reported in Osaka, Japan—where corporal punishment is also used—in 2013.

In light of the potentially destructive consequences of corporal punishment, it may be tempting to celebrate attempts at banning all corporal punishment, but doing so may be naive. Laws concerning corporal punishment have rarely been fully enforced. Legally speaking, the Ministry’s revision of Seoul’s ban on all corporal should have been a restoration of the status quo since direct corporal punishment had officially been illegal for over a decade at that point. However, the lack of an efficient enforcement mechanism meant direct corporal punishment was still widely practiced. Thus, it is possible that there would a lengthy lag between the implementation of a ban on all corporal punishment and the enforcement of such ban. Additionally, teachers’ concerns over class sizes and time constraints should not be ignored since the turbulent period during the 1990s shows rapid disciplinary changes without appropriate teacher training could have negative consequences. Any drastic change in education policy could have unforeseen consequences, but especially in the case of corporal punishment in Korean schools it is important to consider the wide-range of pedagogical and ideological concerns.