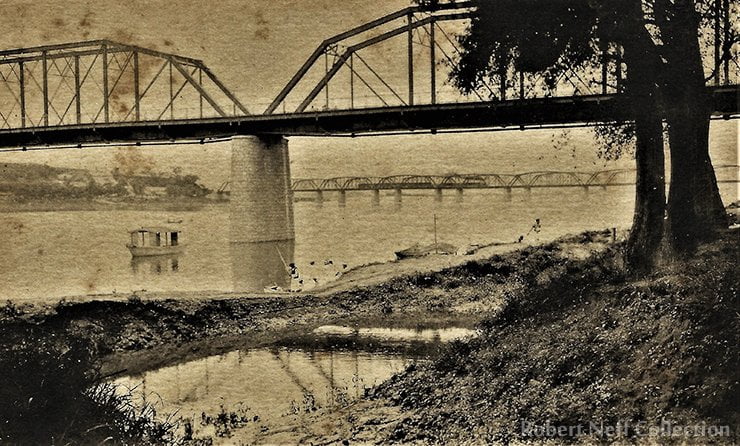

A little over a century ago, land travel in Korea was fraught with difficulty. There were only a few roads—generally nothing more than rough trails—that connected the larger cities. To transport goods, most instead took more watery paths: ferryman take you on ferries across Korea’s wide and winding rivers.

One of the chief riverboat building centers in Seoul was at Noryangjin. Here, boats as large as eighty feet long were built, mostly out of pine. Numbering in the hundreds, these boats were used to transport firewood, rice and other much-needed commodities from Jemulpo (modern Incheon) and the various river ports to the capital.

The Han River was notoriously dangerous for its constantly shifting sandbars and barely submerged rocks. While most of the smaller Korean ships were aware of the rocks and were light enough to avoid stranding on the sandbars, the few Western-built steamships were not. It was all too common for river steamship passengers to end up walking from Jemulpo to Seoul.

Piracy was another problem. There are several accounts of Korean pirates attacking and plundering Chinese and Japanese junks as they traveled along the Han River. The crews were often killed.

The riverboats were usually manned by a crew of three or four men who tended to be, naturally enough, a superstitious lot. The rivers were thought to be haunted by the spirits of the drowned or plagued by dragons who laired in the deeper, darker pools.

One of these haunted places was Son-dol Mok, located near the mouth of the Han River. It was occupied by not only the restless spirit of a wrongly-executed ferryman but also a series of rapids and whirlpools. According to legend, during the Mongol invasion in 1232, King Gojong of Goryeo (reign 1213-1259) hired the ferryman Son-dol to guide him to Ganghwa Island in search of safety. It was at the spot now known as “Son-dol Mok” that the ferryman apparently became lost.

The king, fearing treachery, ordered his hapless guide to be decapitated. Son-dol is alleged to have told the king that even in death he would continue to guide his monarch to safety if the king would have a gourd placed in the water in front of the boat and then follow it. But Son-dol’s professed loyalty was not enough to spare his life and he was promptly executed. Soon, however, the desperate king reconsidered his actions and had a gourd placed just as Son-dol had suggested. The gourd promptly led the monarch to safety.

With deep regret, and undoubtedly some fear that the spirit of the boatman might haunt him, the Korean monarch had Son-dol’s body honorably buried and a shrine erected so that yearly sacrifices could be made on the twentieth day of the tenth month — the anniversary of Son-dol’s death.

As late as 1902 it was rumored that on the anniversary date a “boisterous whirlwind” blows through the area “and the passing boatman is fain to pour a libation and breathe a prayer to the restless spirit of the dead.”

Boats continue to ply the rivers of Korea, but they are no longer the quaint and cautious vessels of the past. Speedboats race up and down the Han towing adventurous water skiers; river-taxis convey the impatient from Yeouido to Jamsil; small yachts serve as status symbols to one’s neighbors. Soon, if the Han River is dredged and the bridges renovated, larger ocean-going ships may once again serve Korea’s capital.

If you enjoyed this article make sure to check out Korean history; The American Empress