Life in Korea during the late 19th and early 20th centuries was hard – physically, emotionally, and spiritually – and often dangerous. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, most Westerners lived in Seoul, Pyongyang, Chemulpo (Incheon), Fusan (Busan) or on the gold mining concessions in northern Korea and lived fairly safe and comfortable lives. But scattered here and there about the countryside were individual missionaries and their families whose lives were trying and often perilous. This is the story of Life in wonju a century ago.

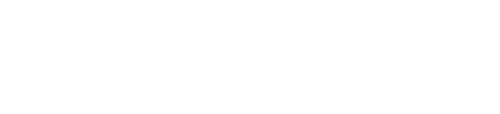

One such missionary was Charles Morris – a Methodist – whose wife, Louise, and two young daughters moved to Wonju in 1916. The Methodist mission first opened in Wonju in 1905 and established the Swedish Methodist Hospital in 1913. It was an isolated and lonely posting with only a handful of Westerners – nurses at the hospital and Catholic priests – living in the region.

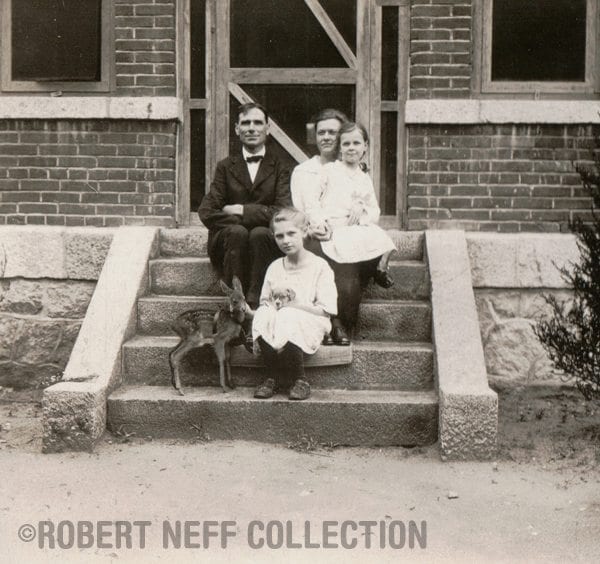

Conditions in Wonju were primitive and the first thing the Morris family did was build a large three-bedroom brick house – complete with a large basement and attic. It even had plumbing – a luxury almost unheard of in the countryside, as told by Muriel Morris, the younger of Charles’ two daughters:

“We had a well underneath the house and the pipes went up to the third floor to the bathroom and there was a pump over the well, and the coolie would go down there and pump and pump until he had sent enough water up to the third floor to last us through the day or for a special bath.”

Unfortunately, it didn’t work very well and the family was content to take their baths in a small tub in the kitchen – the water carried to the tub.

One of the disadvantages of having a large modern home in a city of “little mud huts” was that everyone wanted to see it. Strangers would suddenly show up and announce, “that they were there for a sightsee” and were usually allowed in. Muriel recalled, “one old gentleman, all dressed up with his long bamboo pipe and his long robes, with his hair up in a little knob on top of his head with his little straw basket hat over it. He saw himself in a mirror, stopped and said ‘Oh, what a handsome gentleman, who is that?’ When we told him it was himself he was looking at, he was really startled. He had never seen a mirror before.”

There was a dark side to living there – the house was surrounded by grave mounds and had a reputation for being haunted.

“Koreans were really afraid to come up to our yard at night because they figured it was haunted, having formerly been a cemetery. So one night a bunch of young blades were out on the town drinking and they dared this fellow to go up there and pound a stake in the ground to let the devils out. And he did. When he tried to leave, he could not move – something was gripping him. He fainted, he was so scared. The next morning when his friends went up to see what had happened to him, they found him there lying on the ground. He had pounded the stake right through his long coat.”

The grave mounds also attracted the attention of the Japanese soldiers who were stationed in Wonju. They used this site as a training ground for their mock battles.

“The soldiers would peek at each other over the mounds and yell blood curdling yells and then run at each other. As a child I was absolutely terrified. For years, in fact until I was married, I used to have a reoccurring nightmare where I was running and running and running with the Japanese chasing me and I couldn’t escape.”

The screaming of the Japanese soldiers was not the only thing that gave Muriel nightmares.

Courtesy of Jan Lewis Downing

“I remember as a child being afraid a lot of the time. There was a lot that was frightening such as the sound of a sorceress beating her drum and yelling to frighten the devils from a sick person, the beggars who roamed the countryside, especially the ones with leprosy with missing fingers and toes who sat on our porch demanding food, the bulls who pulled the oxcarts and occasionally went mad and broke loose and ran down the road bellowing, the half-starved Korean dogs who were never shown any affection and were vicious and menacing, and the insane who roamed homeless or were placed in cages in the family’s yard.”

Fears and descriptions of the filth of the community – raw sewage and the reek of human waste used to fertilize the rice fields – often dominated Muriel’s recollections of life but not everything was bad –, especially Christmas, which she found to be a very exciting time and seemed to erase the hardships experienced throughout the year.

“We always had a big Christmas tree decorated with paper chains and popcorn and real candles in little metal holders. It smelled so good and it was so wonderful. We hung up our stockings in front of the fireplace. We would go to bed all excited at night, and the next morning about four o’clock, as soon as it got a tiny bit light, we were awakened by voices singing under our windows. It was the angels singing. I can remember getting out of bed and running over to the window freezing cold and shivering, to see the Koreans from the church who had come up to celebrate Christmas morning.”

Reverend Morris spent the rest of his life in Wonju living amongst the people he came to help and love. His daughter, Muriel, became a teacher at the American gold mining concession in northern Korea and married an American miner – they remained in Korea until the late 1930s. The Morris family’s interest in Korea lives on through Muriel’s daughter, Jan Lewis Downing, who lives in the United States and was kind enough to provide me access to her family’s photographs and memoirs.