Urb-Ex: Far from Abandoned

Urban Explorers Discover What the Country Left Behind

Note: many of the subjects interviewed in this story appear under pseudonyms or modified names to protect their interests.

The crunch of thick glass shards underfoot permeates the corridors, and the roar of the city falls to a muffle through mold-covered walls. Wafting from somewhere nearby is that unmistakable smell… must and ruin. Somewhere above, on a rooftop overlooking it all, stands Jon Twitch, unfazed by the endless blocks of destruction surrounding him.

Jon is one of Korea’s foremost engagers in urban exploration – the exploration of manmade (and usually abandoned) structures. Like a number of other foreigners and Koreans throughout the peninsula, he spends a good deal of his weekends adventuring in abandoned neighborhoods, schools, rooftops, tunnels, or any other mostly past-their-prime locales one is not usually meant to see.

The hobby, while perhaps unfamiliar or strange to some, is popular globally, and the process often comes naturally to those who frequently engage in it.

“Nowadays, it’s become a major process in how my brain works,” explained Jon, a Canadian and 21-year resident of Korea. “I’m always aware of corners and walls that could be hiding some secret, and I’m always ready to pull out my flashlight and duck out of sight.”

Urban exploration is becoming more common of an activity now in the internet age, with a list of “10 Most Fill-in-the-Blank Abandoned Places” circulating every other week. But it turns out that few who engage in this activity even know that what they are doing has a name or choose to use that name.

“There’s just something about the term ‘urban exploration’ as well as its abbreviations ‘urbex’ and ‘UE’ that doesn’t roll off the tongue well,” Jon admits. “It’s misleading because a lot of urban exploration finds are not in urban areas, and we’re not really exploring in the sense of discovering new things.”

Globally, the practice also adopts such monikers as “building hacking” or “infiltration,” while among the more prolific urban explorers in Korea, it comes to be known as everything from “recreational trespassing” to “urban documentation” to simply “adventuring.” One Korean urban explorer even called it “Godzilla-ing”: “Because of broken buildings and strolling in them, occasionally breaking more stuff,” explained Young-gun, a Gunsan resident.

However, it is not just the hobby’s terms that are diverse. Those doing UE in Korea cross genders, race, nationality, age, and goals. Some have had a thirst for the wonder of abandoned exploration since childhood, while others only discovered it in recent years. Some do it for the thrill, while others do it for the discovery of something more.

“It’s such an adrenaline rush,” explains Dominique Le Breton, a South African living and exploring on Jeju. “My parents would always stop outside empty houses and jump over walls and try to get in. They’d discuss the layout of the house and which room was which. I think this sparked some sort of flame in me.”

Another female explorer, Jaeyoon, explains that she came upon urban exploration later in life as a freshman in university, but delved into it extensively from that point on.

“I hadn’t even known such a thing existed but thought the concept was cool,” Jaeyoon, a native Korean based in Seoul, notes. “You are exploring, yes, but instead of new and unplotted lands, you get to look at old and ‘displotted’ locations. My appreciation for photography, memories, and adventure were all able to culminate into this singular activity.

“I do it because Seoul changes every day, so it’s neat seeing locations there one day, abandoned the next, and completely gone the one after.”

Others claim less purpose and more thrill-seeking.

“I’m just a sneaky [guy] who loves the feeling of finding things and then getting in and out unseen,” says Niall Ferguson, an American explorer in Jeollanam-do. “To claim I’m anything else would be bulls**t.”

This thrill of successfully finding a spot, possibly a forbidden one, investigating its nooks and crannies, and escaping unscathed, is undoubtedly one necessary piece of the puzzle of this hobby, most explorers would agree. As “Jenny,” an anonymous Jeollanam-do explorer, puts it, “You just have to try a doorknob and you’re into a magical abandoned world.” But Jenny, like most others, also admits there is something much more significant to the process. Urban exploration, she says, often amounts to near-past archaeology, unearthing and documenting (through eyes or photographs) that which has been or which would be forgotten to the outside world.

“Sometimes you’ll go into a room and you’ll find a person’s entire life,” she says. “…where did they go? What are their stories? If we shared a common language, and I met them, would we even be able to talk about these things? They’re really like archaeological mysteries.”

“Naturally, you get a sense of desperation or gloom when you come across really personal things like photo albums,” Jaeyoon similarly notes. “I understand old toys and clothes, but with old memories, you start wondering why. Were they in a hurry? Could they not afford to take these items with them? Or did they just want to forget?”

The stories and the items may often be depressing or perplexing, but they undoubtedly add a vital component to the interest of urban exploration. Explorers in Korea relay finding everything from baptismal photos to scientific specimens to forgotten sex toys in abandoned locales on the peninsula, all left to the ravages of time and strangers.

“The items inside a place definitely help tell the story,” says Joseph Jung, a Korean-American urban explorer. “An empty school building is just an empty school building, but if you find a bunch of old accordions inside the music room, for example, that tells a story, which could differentiate itself from other similarly abandoned schools.”

What’s the strangest or best location you’ve ever explored in Korea?

“There’s a nondescript house here in Gwangju belonging to a (presumably deceased) Korean shaman who was a hoarder of Buddhist tchotchkes. The house is stacked with religious junk and has remained unchanged in the years since he either died or left. To add to the bizarreness, there are bamboo plants miraculously sprouting up through the ground inside the house.” –Niall, United States

These locations surely do bring stories and questions, but the questions are not just of the past. There is also the question of now—what respect is afforded to these places and what lines should not be crossed there? When is a space off limits, and which items should not be taken or touched? Such questions loom large in the minds of urban explorers, and despite some variations among their boundaries, most agree on the same general ethical rules. The mantra “Take only photos, leave only footprints,” or some variation thereof, is cited often among those in the community when explaining their practice.

Joseph says, “If you start deviating from that code, it’s a slippery slope down and it’s not long before you start justifying taking items, or damaging property. A successful exploration would be to get in, take your pictures, and get back out without a trace of you having been there.”

“I want to take a lot of things,” Jenny notes, though she explains that she actually does not. “We’ll pick things up and we’ll move them around. I’ll also put them back.”

Jaeyoon also feels that moving items is not improper, to a certain degree, but expresses a strong objection to “destroying locations or taking objects outright, including graffiti.”

“I explore for the thrill of getting in and seeing what kind of story has been left behind,” Jaeyoon says, “so if I take anything, then whoever comes in behind me doesn’t quite get the full story.”

As one of the most active and outspoken urban explorers in the region, Jon stresses that those who deviate from the accepted codes are not urban explorers, but just “people in an abandoned place.” In his view and that of many others of his kind, looters, graffiti artists, and vandals of any degree do not overlap with true urban explorers.

“It’s best to leave these things where you find them,” he says, “mainly out of respect.”

But getting in? That’s another story, one full of grey areas depending on the explorer. And for many urb-ex enthusiasts, regardless of their rules, getting in is the best part.

“If a place is locked tight, I’ll try again later and hope something changes,” Jon says. “But ‘No Trespassing’ signs don’t scare me away. … I’ll think nothing of climbing through windows or scaling walls. Lately I’ve even been looking into the safest ways to scale traditional Korean walls, which pose their own unique difficulties. If it isn’t causing direct harm and I can get in and out without being noticed, that’s fine by me.”

“When I was a teenager, I had no scruples whatsoever,” Niall explains. “The further I get beyond peak testosterone, however, the more I become a derelict-hugger. I still ignore most signs, force open doors, and climb walls, but I don’t break or take much anymore.”

Most of the explorers interviewed had no qualms about scaling a wall or fence or about undoing one of Korea’s ubiquitous construction curtains. Some also admit to unhinging windows or unwiring closed entryways, though many also choose to redo these features when they leave.

“Things are not guarded here,” explained Jenny, who carries a multi-tool when adventuring to aid in entry. “It’s just really easy to walk in. But sometimes, once you’re in, there’ll be things that are wired shut. I have no problem unwiring those things.”

What’s one of the strangest things you’ve found in an abandoned locale?

“I found a specimen collection of various animals in jars. One was a nervous system including eyes, brain, and nerves. I had nightmares about that thing. At first I didn’t know what animal it was, and later when I was at home in bed with my cats, I looked closer at a picture that showed the jar labeled as a cat.” -Jon, Canada

All of this, though, raises another important question to urban explorers: what if you get caught? More than most other urban explorers in Korea, Jon notes a range of encounters with police and authority figures, as well as locals, all fortunately ending without legal incident.

“I’ve had too many confrontations and encounters to count,” Jon says. “A lot of people don’t like me being around abandoned areas, whether for safety, political, legal, or national image concerns. They might yell at me, or ask what I’m doing, or politely ask me to leave, or just make a small sound of disapproval, or not do anything.”

None of the subjects interviewed suffered major legal ramifications for their explorations. But the possibilities of such things happening remain as one of the dangers in urban exploration.

Juwon Kang, a Korean lawyer running the blog klawguru.com, cited several articles of the Punishment of Minor Offenses Act that might apply to urban exploration. Among them, one clause notes detention or fines of up to 100,000 won for “any person who breaks into an uninhabited or abandoned house, or breaches a fence thereof, or enters a structure, ship or car, without justifiable grounds.” Furthermore, while the majority of urban exploration adventurers insist they would not harm property on purpose, doing so accidentally is always a danger—one which could cause even further problems. Kang notes that Article 366 of the Criminal Act could theoretically affect anyone destroying even abandoned property, and even accidentally, with potential consequences of up to 3 years imprisonment or seven million won in fines.

Legal implications, though, are generally of less stress to urb-ex practitioners than safety concerns are. For this reason (among others), Jenny explains, it’s better to share the experience with others and be responsible for each other.

“The thing that we do is not safe,” she reiterates. “We have a high-risk interest. There are many, many times when I trust my instinct and I have to stop.”

Korean urb-exers tell stories of breaking ice, falling through floors, and even getting trapped inside locked locations. Less immediate than the occasional accident, though, is the threat of poor or contaminated air, which is perhaps just as dangerous. The risk of chemical, asbestos, and mold exposure is not taken lightly by many urban explorers.

“You open a building and it’s like ‘oh, it’s that smell’… no one’s been in here in a long time,” Jenny says. “But oftentimes I feel sick for about 4-5 hours after I go because of the sheer amount of mold and mildew.”

“In terms of injury or illness, I got really sick after exploring a site with a lot of bird droppings,” Joseph relays. “I spent a night at a local hospital alone and I wasn’t able to really explain to the doctor what I was doing or what possibly made me sick. I now pack a respirator with particulate filters whenever I go exploring.”

All of these factors add to the danger (and perhaps the thrill) of urban exploration, but they don’t lessen the advancement of the hobby. Particularly in Korea, which many explorers view as an ideal and underrated base for the hobby.

Part of what makes the country a delight for urb-exers is the relative safety and lack of concern from onlookers.

“It helps that laws are generally more lax and people don’t tend to carry firearms,” Jaeyoon says. “My perception of threat is much lower in Korea than in the States, whether from policemen, security guards, or the homeless.”

“Security and legal concerns are lesser here,” Jon confirms. “People just aren’t aware of it, so for those who want to try exploring abandonments, draining, or rooftopping, there are some unbelievable opportunities.”

Beyond the attitudes, though, Korea has begun to gain a reputation as an urb-ex destination due sheerly to the abundance and range of its abandoned venues. Among the most well-known destinations, Geonjiam, an abandoned mental hospital, has been documented prolifically online, as have amusement parks such as the notorious (and now-demolished) Okpo Land.

“We’ve developed a bit of a reputation as a place to visit abandoned amusement parks,” Jon explains. “I heard from a European explorer who visited Korea recently, and I think he was able to visit four abandoned amusement parks within one week.”

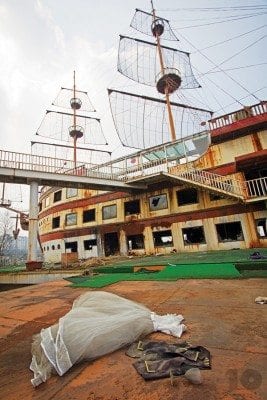

But theme parks are just the beginning. Northern Gyeonggi overflows with abandoned period movie sets. The east coasts hosts everything from derelict ski resorts to disused army barracks. North Jeolla boasts a giant, rusting wedding hall in the shape of a ship looming over a rice paddy. And Jeju? Jeju seems to stand as a mecca for Korean urban exploration, offering old schools, abandoned resorts, a famed castle, a crumbling circus, and more all the time.

Beyond the most famous and striking sites in each area, though, most explorers note that, despite the “urban” in “urban exploration,” societal factors often cause rural areas in Korea to be just as ideal for many of these adventures as the ever-changing neighborhoods of Seoul.

“Demographic decline in the countryside is fascinating to see up close,” Niall notes. “You always hear about crashing fertility rates and urbanization having a major impact on rural places, but to see so many schools left to fester in the fields always brings it home. Then again, I’ve seen quite a few of these schools get repurposed as art studios, farms, apiaries, galleries and local repositories, so it’s not all doom and gloom.”

With such an abundance of locations, both urban and rural, many of the more hardcore explorers note that scouting and finding the locations—finding your own locations, even—can be one of the most gratifying aspects of the hobby. This also leads to one of the final commonalities among true urban explorers: a general reluctance to share locations with more than a trusted few.

“A large amount of work in urban exploring is in researching and scouting new locations, and I tend to only share location information with others who have something to share back,” Jon explains. “If I’m going to go out on a limb for you, I want to make sure I’m not dooming the location to overexposure or dangerous activities, or putting you at risk of injury or legal troubles.”

Some frequent urban explorers in the community are more open, though they rarely post locations on public blogs. Dominique notes that on Jeju, there is a richly connected group of enthusiasts who share new spots with each other freely, and many of the explorers on both the island and mainland express a willingness to show others the locations in person.

“If I find something awesome, I will take an adventure partner and show them,” Jenny says. “But I wouldn’t post it anywhere. I don’t think I’m all that just because I found something. Some people just guard their sites pretty ferociously. Maybe because they’re special.

“What we do is special.”

“As more people come into the hobby, I do my best to raise awareness of the risks and ethical considerations,” Jon Twitch concludes. “My network of trustworthy explorers based all around Korea has grown considerably and we are always recruiting sensible people. As far as the higher number of people getting involved, it’s just a bit of added challenge to stay ahead of the herd. If there are more people getting involved, I’ll just go to another level. That’s sort of how I got into exploring in the first place.”

You might walk by these locations on your way to work every day without a second thought, or zoom past them on the train or bus without any urb-ex delight. Next time you see a derelict structure looming over the land, though, know that someone like Jon Twitch may have been or may now be inside, crunching over broken glass in search of a special slice of life forgotten.

For more information on the interviewees or Urban Exploration experiences in Korea, please visit the following:

Jon Twitch: www.daehanmindecline.com

Niall Ferguson: viakorea.wordpress.com