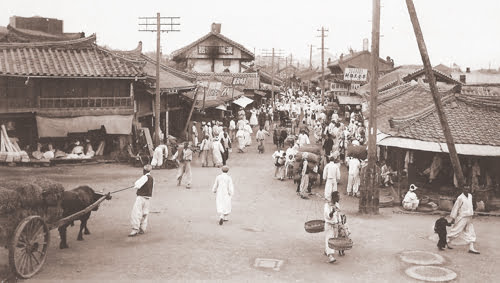

Photos courtesy of the Robert Neff collection

The anti-Western sentiment pervasive in Pyongyang today has a long history, as historian Robert Neff recounts.

Much as it is now, Pyongyang in the late 1880s and early 1890s was pretty much anti-Western. The legacy of the General Sherman in 1866 gives testimony to the residents’ stoic opposition to all things Western. The General Sherman was a ship that traveled up the Taedong River to the city, despite being warned not to, and was then subsequently destroyed. The city was and presently is a bastion of conservatism and unwillingness to accept change.

Anti-Western sentiment in 1890s Pyongyang

There were few Western visitors, the only exceptions being the occasional French priests and American missionaries. One of the earliest American missionaries was Samuel Moffett. It is through his writing that we get a candid glimpse of the city in the early 1890s and the troubles associated with being a foreigner. His visit started out uneventfully:

“The streets we found to be as usual narrow and filthy, and crowded with shops of native wares. The people whom we had often heard to be more warlike and independent than other hermits seemed to us in their appearance and disposition a very ordinary lot, perhaps a little less noisy and somewhat more polite than the natives of the south.”

But that initial opinion changed relatively quickly. For about a week Moffett and his companions lived quietly in a Korean inn, but whenever they went out onto the streets they “were followed by an innumerable company of spectators, whose outbursts of laughter as we walked along seemed to betoken something extraordinary in our personal appearance.”

Moffett and the subsequent missionaries felt insulted by the Koreans’ reaction to their presence. Sometimes it wasn’t just jeers and insults that were hurled. The Koreans in this region were very skilled stone-throwers and the missionaries found themselves the targets on more than one occasion. Sometimes, though, the missionaries may have been partly to blame.

Faults on both sides

James Scarth Gale, a Canadian missionary, seems to have taken more than a few liberties with his Korean hosts. Once when confronted with a shallow but swift mountain stream, Gale hailed a nearby Korean coolie [porter], asking him to kindly carry him across in return for pay. The Korean refused and told Gale to make his own way across and then started to ford the stream alone. Gale, shocked at the perceived impertinence of the coolie, suddenly jumped upon his back and would not let go. The coolie “muttered to himself awful threatenings, proceeded slowly, stopping to reconsider in the middle of the stream, but it was hopeless and so he landed [Gale] safely.”

Gale promptly offered his apologies and a fairly large amount of money as a form of indemnity. Years later Gale wrote: “He (the coolie), however, stood looking at me in speechless amazement and is standing so yet for aught I know.”

But this wasn’t Gale’s only imposition. Later, he and another missionary (perhaps Moffett) found accommodations at a small inn operated by an elderly couple. The wife was extremely nice and told them that she knew Westerners were good people and there to help the Korean people and not harm them. According to Gale, “this was encouraging, like rain on thirsty ground, after being pointed out for weeks as foreign devils.”

Gale discovered a fishing pole in the inn and decided to do some fishing while away in the afternoon. Gale considered himself part of the family and could see no reason why he should ask anyone for permission to use the pole—but he was wrong.

Making his way down to the river he cast the line in. Suddenly, as he recalls, “I felt a shock, not from a bite, but from a call behind me to bring home that fish rod. I pretended not to hear. The storm would blow over in a little [while].” Unperturbed, he resumed fishing and was excited when he felt a bite but then “a whirlwind suddenly caught me, in which I lost line, fish, interest and everything. When I came properly to, an old Korean, seventy years of age, was carefully putting a fish-rod back in its place…” Gale had been taught a lesson.