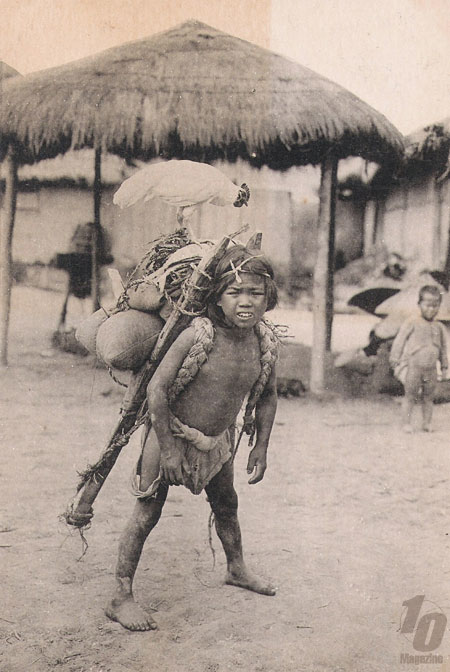

The children of Joseon. Korea may not have had a holiday dedicated to them, but they still had to shoulder heavy domestic and scholastic responsibilities like their counterparts today.

Words by Robert Neff, Pictures from the Collection of Robert Neff

In the late Joseon period, young Korean boys and girls were often found in the streets playing together “wearing nothing more than a smile.” During the summer, little boys and girls alike wore nothing more than a short shirt which hardly covered their nether regions. This may also explain why the Korean phrase bural chingu (“憲耀掘, which translates literally as “testicle friend”) is used to describe an old childhood friend. This behavior was so prevalent that one American missionary declared Korea to be “a land of naked children.”

But this children’s version of the Garden of Eden all ended around the age of seven. At this point, boys and girls were separated from each other. Little girls were sequestered to the back of the house where they played “at sewing and keeping house at the dreary washing that may soon become their lifelong toil.” The only males who were allowed to see them were members of their family.

Little boys either went to work or to school. There are many pictures from the late Joseon period showing young boys peddling goods such as candies and water along the streets of Seoul or driving oxen laden with goods and firewood to market. For the most part, they appear to have been happy despite the rough life they lived.

For the gifted or those from wealthy families, school was an inextricable part of daily life. From early in the morning until late in the afternoon the young scholars at the traditional schools studied the Chinese classics while those who were fortunate enough to attend the Western schools sponsored by the Korean government or by missionaries studied various subjects including foreign languages, math, sciences and history. As in the present, these young men were the hopes of their families for a better life.

At some point most boys married – those who did not, despite their age, were considered boys and would be treated as such. Most marriages were arranged, usually while the brides and grooms were yet in their teens. The bride’s lot was one of harsh contrast. Western missionaries relate that on the night of the wedding, young Korean brides often cried uncontrollably, filled with sorrow at being separated from their families and apprehensive of their lives at their in-laws’ homes. On the day of their wedding, they were required by Korean custom to remain perfectly silent and to display no emotion at all – despite the villainous efforts of their in-laws.

While many things have changed over the past century in Korea, the freedom of youth is still undeniably short. At younger and younger ages, Korean children are forced to study. They endure long hours at school followed by academies, and even at home they are not free from lessons given by private tutors and educational programs on TV. There can be little wonder why May 5th of every year is one of Korean kids’ favorite holidays. Children’s Day is one of the few days that they can just be children and play to their heart’s content.