In 1885, Percival Lowell published a book entitled “Choson: The Land of the Morning Calm.” It was a huge success and helped coin the phrase that is still often used to describe Korea. But when the first Westerners arrived in Seoul in the early 1880s, it was anything but calm. It was a realm devastated by cholera, smallpox and political unrest – plagued with revolts and assassination attempts. And, according to some, it was filled with ghosts.

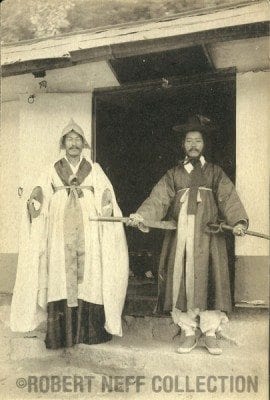

When the first Western advisor to the Korean government, Paul Georg von Mollendorff– a German, arrived in Seoul in 1882, King Gojong found himself in a quandary as to where to house him. The recent Imo Revolt had left many large compounds empty – their former residents were literally butchered in their homes – and in the months following the massacre, these homes gained the reputation of being haunted. One such compound was that of Min Kyomho (1839-1882) who had played a key role in sparking the revolt which he and his family paid for with their lives. The locals were afraid to go near it because of the alleged sightings of a white apparition that haunted the area.

Despite his misgivings, King Gojong directed that Min Kyomho’s compound be provided to von Mollendorff and his family. It is unclear if von Mollendorff was aware of the rumors concerning his house (I believe he did), but apparently he was unbothered by them or the ghosts and stayed in the house for about a year before moving to a better residence.

But von Mollendorff was not the only one to dwell in a house with a haunted past. While many Koreans refused to dwell in these haunted abodes, newly-arriving Westerners found them to be ideal.

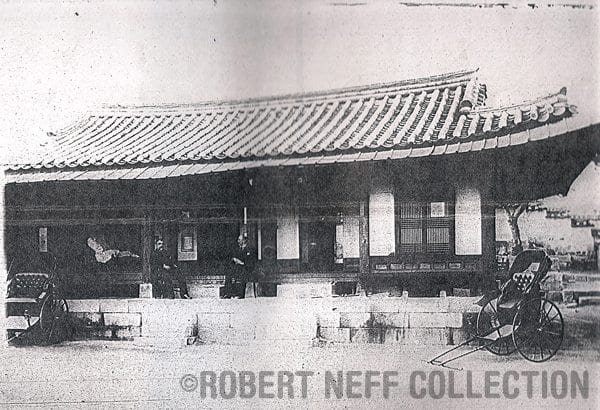

American Minister to Korea, Lucius Foote, and his wife, Rose, arrived in Seoul in mid-May 1883 and managed to purchase the former

“abode of one of the Queen’s powerful family” for a mere $2,200. One of the reasons Foote was able to get the property so cheaply was because it, and many other homes that were later sold to Westerners, was believed to be haunted. According to a family friend, the compound had “a most fascinating history and was invested with the flavor of romance. There were proud, surviving interests in gruesome tales of its valiant decapitated Mins, who even now in unquestionable shape, periodically stalked about the premises.”

Despite the property having once been an “ancient Min palace”, Foote’s description to the State Department was seemingly negative. A newspaper described the Footes’ lives in Seoul as one “attended with many discomforts and privations. The only house [they have] been able to obtain is a rude one of wood and paper, with paper windows, and is situated in an undesirable location in the midst of hovels and filth.”

Rose immediately set out to put the legation in good order and had repairs made both internally and externally. Walls were repapered and murals painted and on the outside Rose had a large garden planted with the aid of Korean laborers and a Japanese gardener. Rose was quite fond of flowers and sought comfort in her gardening but even this tranquil pursuit was tinged with the macabre. Rumors circulated amongst the Korean staff “that skulls and headless skeletons [victims of the Emo Revolt] which had missed honorable burial, had been turned up in the gardens.”

Despite the evil associated with the gardens, they flourished and soon Rose’s flowers graced not only the tables as ornaments but also as garnishment on cakes and other treats to the palace.

The Footes were not the only ones to take advantage of the Korean’s fear of ghosts. When Horace Allen, the first Presbyterian missionary to reside in Korea, arrived in Seoul in 1884, he noted that “the foreigners here have purchased places formerly occupied by noblemen who were killed in the revolt some two years since. As the buildings were supposed to be haunted they were sold quite cheap.” He quickly bought an estate but it isn’t clear what its alleged haunting status was.

Even the streets were said to be haunted by Korean ghosts and, surprisingly, even a Western ghost or two. One account claimed that a creature with “a white, yellow hair, blue eyes, and blood-red lips, and cried in a child’s voice” stalked the streets abducting small Korean children.

There were other menaces to the peaceful sanctity of Westerners in their homes. Brash noisy magpies built their nests in the gardens’ trees and from their lofty perches espied coins and other shiny things which they promptly snatched. Efforts to approach their nest – either by humans or cats – were met with dive-bomb attacks.

Birds, mainly sparrows, built their nests in the rafters where they raised their families in the summer-time, but come winter these nests often proved to be fire hazards. Rats, too, built their nests in the rafters and their nightly escapades scared more than a few Westerners. Elizabeth Greathouse, whose son was an advisor to the Korean government, complained that she could not sleep at night because of the rats that kept trying to gnaw their way into her room. She tried to scare them off by ringing a bell but they were undaunted. She finally resorted to brushing tar along the rat’s path in hopes of trapping it in the sticky liquid. She had mixed results but she did have an unexpected ally – the snake.

Snakes were often found in the rafters where they hunted rats and preyed upon the eggs and chicks of the birds. Of course, during the summer, these snakes occasionally fell victims to their prey. According to Horace Allen:

“On bright warm days in the spring these snakes often come out upon the roofs to sun themselves, where they are soon discovered by the sparrows that regard them with just hatred, and they begin a most excited chattering and dashing at and about the snake. Messengers fly off and collect companies of the valiant magpies that certainly do enjoy a fight, and they soon drive the snake to cover by their vicious pecks.”

Snakes were generally left alone by their human hosts because they kept the rat and bird populations in check but, at the palaces, if a snake should drop into a room from the rafters, it was viewed as an ill omen and the building was abandoned.

Considering what we know about Korea’s past and present, “The Land of the Morning Calm” seems more and more like a misnomer than an accurate description of this beautiful and vibrant but troubled country.

Words by Robert Neff

Photos from the Robert Neff Collecion