The Korean war effectively leveled the Korean Peninsula. The South Korean people were left homeless and without even the most basic elements of infrastructure; schools, hospitals and businesses had to rebuilt from scratch.

Some notable exceptions include a few of the sturdier and luckier Japanese-built imperial buildings constructed during the occupation that managed to survive the civil war.

The Building Process

At the end of the war, the U.S. invested a record amount of money, ostensibly to help the Korean people but, more precisely, to use the 38th parallel as a bulwark against the red tide of communism that China and USSR represented.

The money was used to help the South Korea modernize and industrialize. Essential repair to infrastructure and urban centers followed, most of it characterized by quick, simple, and cheap design.

Over the next 40 years, with the continued help of American investment and a few ambitious military strongmen, the South Korea housed itself.

Traditional Hanok villages were razed to make way for pragmatic, sterile, uniform buildings. Hospitals, schools, and industries began simple construction under the guidance of engineers and architects with no priority for Korean architectural traditions or long term sustainability.

We can see the results of this post war architecture everywhere in South Korea. The majority of Korean cityscapes are dominated by rows of utilitarian tower blocks known as danji (단지).

The Designing Process

Despite multifarious diplomatic issues with its neighbors, economic setbacks and internal political brouhaha, South Korea has become a solid member of the G20.

With one of the world’s strongest economies, both the government and private enterprise have in the last decade begun to invest in better design. Local architects, having trained abroad, returned to their native country to implement more sophisticated design and construction techniques.

Celebrated foreign architects were either invited or submitted their own proposed plans for major projects backed by increasingly impressive budgets.

Progressive, inventive and often strange constructions have sprung up, some of them better than others, but all of them contributing to the morphing of South Korea’s landscape.

The List Of Contemporary Architecture

Below is an arbitrary list of South Korea’s most impressive contemporary architectural buildings and spaces.

They were chosen for their ability to impress and their relatively open access to the public. Each of the following spaces can be appreciated by the erudite architecture buff or the inquisitive tourist.

10. Seoul’s Floating Islands

Much like the designer handbag is coveted by the Cheongdam débutante, so is a new architectural landmark desired by the megalopolis mayor.

The Floating Islands are former Seoul Mayor Oh Sae-hoon’s baby. There are three separate man-made floating islands: “Vista” contains a performance hall and a moonlight trail.

“Viva,” meaning “cheers,” is purported to be the entertainment island and has a variety of culture experience facilities. And finally “Terra,” despite its name, is the island meant for water leisure.

They are all, though not always, connected by pleasant bridges and are best visited at night when illuminated by colorful light shows.

(source)

9. Haeundae Udong Hyundai I’Park

Controversy follows starchitect Daniel Libeskind wherever he goes and with whatever he designs. The imposing size and design of this megalopolis monster is both eye-opening and intimidating.

The six new towers are sculpted to express the dramatic beauty and power of the ocean. The curvilinear geometry of the buildings plays with concepts of traditional Korean architecture.

Often derived from natural beauty such as the grace of an ocean wave, the unique composition of a flower petal, or the wind-filled sails of a ship.

(source)

8. Saetgang Bridge

The Han River has a plethora of bridges, some of them quite impressive, but the jewel of the bunch is likely one of it’s shortestand least used.

The Saetgang Bridge connects Yeoido island with the proximal southern shore. The Saetgang is an asymmetrical cable-stayed pedestrian bridge.

The swerving bridge is supported by a series of off kilter cables that result in angles that both the architectural aficionado and ignorami can enjoy. It can be visited anytime by anyone.

(source)

7. Ehwa Womans University, The Campus Valley – ECC (Ewha Campus Complex)

A preponderance of vertical architecture dominates most cityscapes. This is particularly true of Seoul, where space is limited and population increase is uninhibited.

The phallic nature of vertical construction is often unavoidable. However, the beautiful and rather hidden main building of this woman’s university is uniquely and rather appropriately vulvic in nature.

Though he hasn’t won it yet, the architect, Dominique Perrault, is a perpetual front runner for the Pritzker prize.

Take a walk down the valley and enjoy the contemporary femininity of the structure and its occupants.

(source)

6. Jongro Millennium Tower

Commissioned by Samsung Securities and designed by super-architect Rafael Vinoly, the Jongro Millenium Tower was completed in 1999.

The tower’s unique construction is supported by 3 cores with exposed steel girders. A dramatic floor gap from the 23rd to 30th floor gives the building some heavy duty feng shui credibility.

At the very top is a café and restaurant, designed by noted French interior designer Philippe Starck.

The views from the Top Cloud Café are charmingly personal and give its diners a much more intimate perspective of Seoul than the stratospheric views from the overcrowded N Seoul Tower.

(source: https://amonthlater.wordpress.com/tag/jongno-tower/)

5. National Museum of Korea

This behemoth of a building is worthy of its status as the National Museum of Korea. It is the sixth-largest museum in the world in terms of floor space and houses over 220,000 pieces.

The museum has state-of-the-art air conditioning and lighting systems and was built to withstand a 6.0 Richter scale earthquake.

The building was designed to both respect and reinterpret the Korean architectural spirit. Like the hanoks of old, the mountains are behind it and the river in front of it.

The main plaza is an architecturally awe-inspiring gateway to the museum’s various display wings.

(source)

4. Jeju’s Glass House

Despite ongoing tensions between Korea and Japan, the magnanimous people at Phoenix resorts still hired the minimally minded Japanese architect Tadao Ando to design the Glass House.

Two restaurants inside have affecting views of the waves crashing over the rocky shores of southeastern Jeju Island.

3. Dongdaemun Design Plaza & Culture and History Park

Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid is the first and one of only two women to have won the Pritzker Prize. There was a bit of fuss when a foreign woman was chosen as the architect for this project, and even more when she faxed in her “Metronymic Landscape” designs without ever having visited Seoul.

However much the building might not fit in, it does add a touch of international class to this grimy neighborhood. With a little luck the plaza should be ready within three years of its original completion date of 2011.

The adjacent park however is ready and provides a pleasant oasis from the chaos of the surrounding areas.

(source)

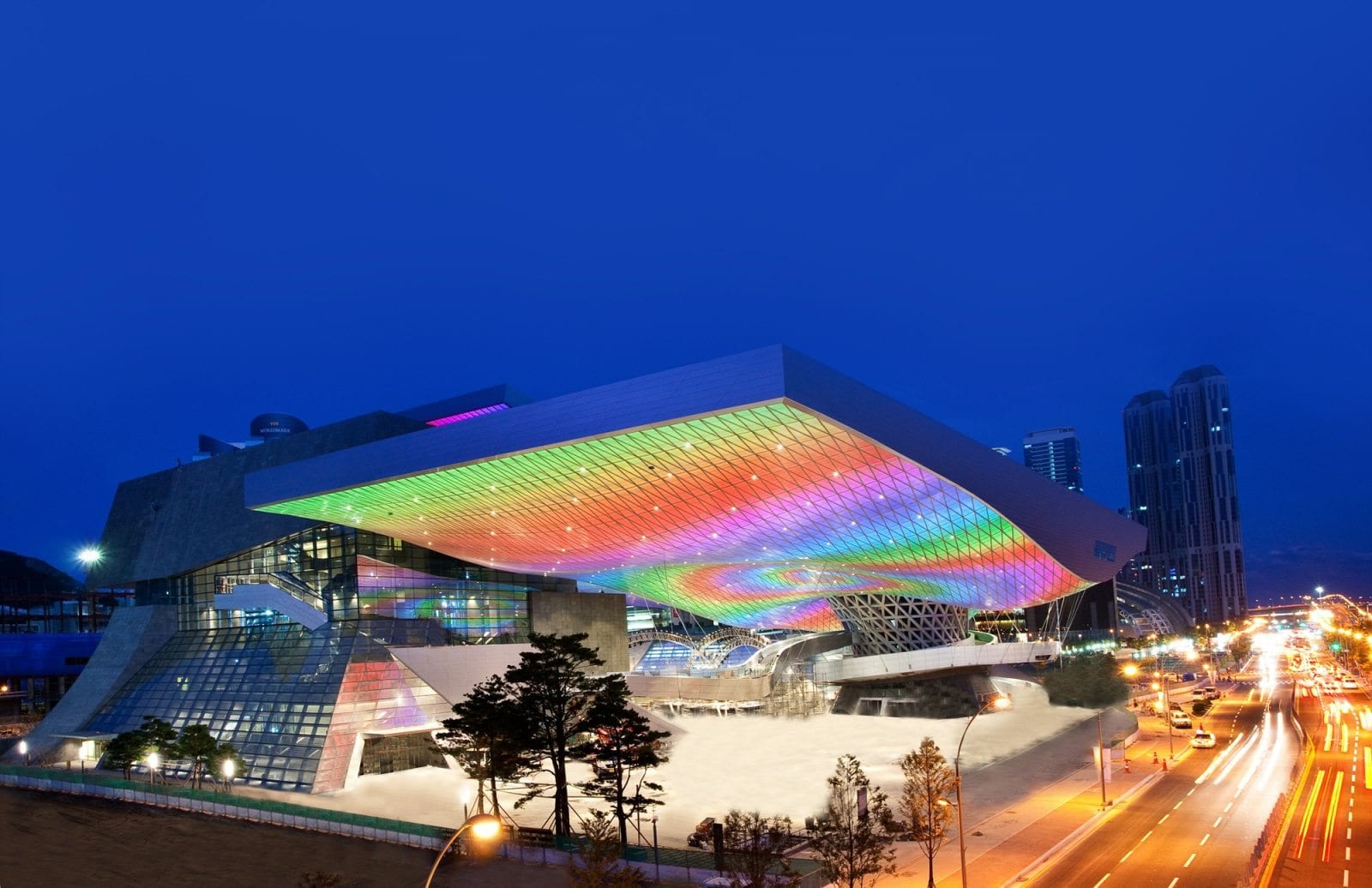

2. Busan Cinema Center

Inspired by the likes of Oscar Niemeyer and Le Corbusier, the Busan Cinema Center was designed by Viennese architectural firm known as Coop Himmelb(l)au.

The “Blue Sky Cooperative” are known for, among other things, their ambitious roofs. The Busan Cinema Center’s roof is, as of this year, the world’s longest cantilever roof.

To watch a movie under this massive unsupported canopy is a unique opportunity to interact with architecture.

(source)

1. Seoul City Hall

Seoul City Hall has played an important role in modern Korean history. Designed by German architect Georg De Lalande for the Japanese colonial administration, the building was a symbol of Japanese imperialism.

In 1995, 50 years after Korea had gained its independence, the building was demolished and “moved” to its current position.

A massive swell of glass now looms over the older, stone colonial section. The symbolism is clear; rather than trying to forget its past by erasing the colonial traces, modern Korea will rise up and over it.