Words by Robert Neff Photos from the collection of Robert Neff

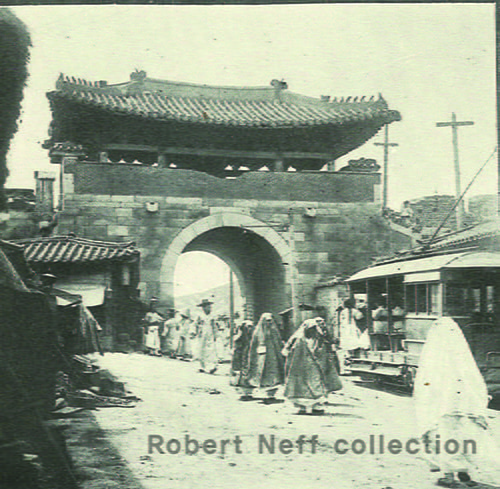

One of the earliest modernizations to Seoul was the introduction of streetcars in 1899 by an American company. It was heralded by many people as a symbol of modernization and prosperity. But not all viewed the streetcars with anticipation and delight. Korea was suffering from a severe drought and many superstitious people thought that the streetcars were to be blamed. It was reasoned by some that the streetcar tracks had been laid across the tail of a great dragon that slept beneath the city. Others claimed that the streetcars sucked away the clouds and thus deprived the kingdom of rain.

Opposition wasn’t confined only to superstitious beliefs—some of it was due to economic concern. Rickshaw operators and coolies (laborers who transported goods on their backs or by oxen) regarded the streetcars as a threat to their livelihood.

The streetcars were supposed to begin operating on May 1, 1899 but were delayed due to some machinery problems as well as the theft of some electrical wiring by five daring Korean thieves, which resulted in the loss of their heads. However, a couple of weeks later the streetcars began running—even though the official opening had not been held yet. The initial ticket sales were extremely promising, with nearly $100 dollars in sales the first couple of days.

On May 26 the opening ceremony was held and well-attended by a jubilant crowd of Koreans and foreigners. However, the celebration was quickly marred when a small child ran in front of the one of the streetcars and was killed. An angry mob rose up and tried to lynch the driver and conductor, who barely managed to escape with their lives. The mob then turned their attention onto the equipment and burned two streetcars.

For several weeks the streetcars ceased to operate, as the Japanese drivers and conductors were too afraid to go back to work. This was solved when the company hired a group of Americans from San Francisco. These men (who came to be known as the California House) were a rough group of cow punchers, gamblers, bartenders and even a professional gunslinger who later got into trouble for shooting the topknots off of Korean pedestrians.

They did, however, have the desired effect and the streetcars were soon running again. In the beginning there were five cars that were divided into closed and open compartments. The closed parts were for the eight first-class passengers while the open parts were for the twenty-five second-class passengers. There was also one closed car for special occasions which could be reserved for “trolley parties”. Finally, there was a personal car for Emperor Gojong which “was richly upholstered with the windows emblazoned with the Korean ensign, while large platforms at either end furnished ample room for the accompanying guard.”

The streetcars played another role in Korean modernization. In an effort to increase patronage, the streetcar company built a small circus in 1900 at the end of the tracks in Yongsan and offered riders free tickets to the performances. Later, in 1904, it purchased a number of movie projectors and built a small theater at the other end of the line—some six miles outside of the walls. Passengers who bought a five cent streetcar ticket and rode to the end of the line were given a free pack of cigarettes and a theater ticket.

The advertising scheme was a great success. Most Koreans—and for that matter, many foreigners—had never seen motion pictures before, and the number of riders increased so much that the company expanded in the summer of 1905. The streetcars had begun an indispensible part of life in Seoul.

__________

Robert Neff has authored or co-authored several books including Korea Through Western Eyes and The Lives of Westerners in Joseon Korea. He currently writes a twice-weekly column for the Korea Times entitled “Did you know?” as well as a twice-monthly historical column for the Jeju Weekly.

__________