As we welcome in another New Year with copious amounts of food and alcohol in homes or at local pubs and clubs, let us pause for a moment and reflect on how the New Year was celebrated by Koreans a century ago.

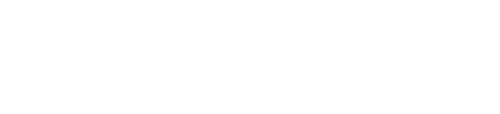

Although the solar New Year – December 31/January 1 – is widely celebrated in Korea, its popularity is relatively recent. Up until the beginning of the twentieth century, only Lunar New Year was celebrated. Then, as they do now, Koreans dressed up in their best clothing and went about visiting relatives and friends for food and drink.

Games were an integral part of the celebrations. Many of these games were oriented towards battle – both supernatural and mortal opponents. Some of the more infamous games have been discussed in earlier articles (such as kite fighting and stone battles) but there were others.

Tug of war (Juldarigi) was a very popular event, especially in the countryside, and often held on the night of the first full moon. Two teams were made up – one representing the east and the other the west – and if the west side won, then the village would have a great harvest. Naturally enough, the west side was favored, but the participants on the east side were usually determined to try and win.

The straw rope was actually made up of two huge pieces – each weighing several tons – and once joined together, the tug of war would commence. The night before the competition, the teams would guard their part of the rope to ensure that the opposing team did not sabotage it either by physical or superstitious means.

Nails or needles driven into a rope were believed to weaken it so that it would break during the competition. It was also believed that if an opposing team member stepped over the rope that it would weaken it. But not everyone tried to step over the rope in order to sabotage it; some did it for their own personal gain. It was believed that if a woman stepped over the rope, she would be blessed with the birth of a son. According to Professor Kim Kwang-on, less than a century ago, a woman, desperate to have a son, was stoned to death for daring to step over the rope.

Once the competition was over, the two pieces of the rope were cut up into smaller pieces and given to the winning side. The straw was believed to have many powerful abilities depending on its use. If used as roofing material, it protected the family beneath it. If used as fertilizer for crops, it ensured a bountiful harvest. And, if given to cattle, it would make them strong and healthy. Professor Kim also noted that fishermen would come and purchase some of the straw thinking that it would provide them with the edge needed to ensure a great catch. As to the losing team – they had to not only endure humiliation but, in times past, may have been required to do work for the winning team.

Swinging was another popular activity. It was an exciting event in which both males and females participated but was generally more popular during the late spring or early summer. At the turn of the twentieth century, Horace N. Allen noted “strong swings are suspended from suitable trees, or if no suitable tree is at hand, massive frames are erected and topped with boughs. On these swings several men will at times perform together. The observance of this custom is supposed to mitigate somewhat the plague of mosquitoes during the ensuing summer.”

Another activity engaged in various seasons was Neotwiggi or seeswing. This was especially popular with young girls. Unlike Western seesaws, the participants did not sit at the end of the plank but rather stood, making it a far more interesting experience.

Not only was it exciting because it propelled the young girls high into the air, but also because it provided them with a view over their garden walls and allowed them to be seen by the young neighborhood boys. It must be remembered that during the Joseon era, girls older than six or seven were sequestered in their homes away from the view of boys and men.

There were several old sayings associated with seesawing. One claimed that if a girl wasn’t able to seesaw well then she would have problems bearing children later while another claimed that if a girl did not seesaw then she would later be plagued with splinters in her feet.

The history of seesawing apparently goes back to at least the Goryeo (918-1392) period and may have been exported to Okinawa by shipwrecked Okinawan sailors or its envoys who visited the Korean court.

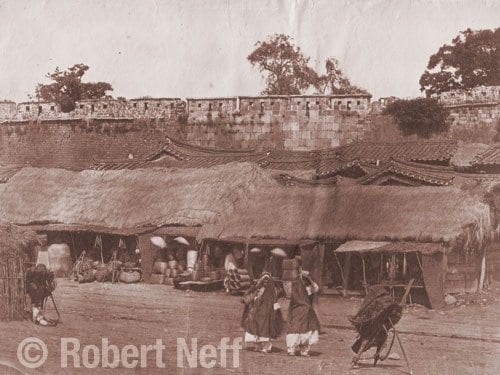

Not all activities were so physical. Gambling was apparently so popular that one early Western visitor declared: “Koreans learn the delights and pains of gambling almost from their mother’s milk. You see little fellows five and six years old pitching cash [Korean coins from the Joseon period] with an eagerness and untiring zeal which shows it is not simply the fun they are after.”

Adults often played games using Japanese flower cards – probably similar to the modern game of Hwatu or go-stop. A Canadian visitor in the early 1890s noticed that “card playing, though interdicted by law, is habitual among the common people. The nobles look upon it as vulgar amusement beneath their dignity. The people play secretly or at night, often gambling to a ruinous extent.”

It seems that many of these early foreign observers were blind to the gambling exploits of their fellow Westerners. Contemporary accounts attest to diplomats and miners gambling at the legations, in their homes and in the hotels and bars of the open ports.

This year why not do something special to celebrate the New Year – something cultural. A trip to the east coast to witness the first sunrise of the year could be both adventurous and romantic. You could go to the large bell at Jongkak (downtown) and join the crowds of people waiting to hear the huge bell toll in the New Year. Whatever you decide to do – we at 10 Magazine wish you a safe and happy New Year.