Author Lisa See had wanted to write about the haenyeo for a decade when she realized that time was running out. If she waited much longer there might not be many women left to interview.

When she began researching her novel, The Island of Sea Women, many of Jeju’s remaining divers were already in their 80s and 90s. Traditionally, haenyeo stopped diving at age 55, handing responsibility to younger women, but for decades there had been fewer women to replace them. Younger women, with more career options, were choosing less dangerous professions, forsaking a way of life that lasted for thousands of years.

“This is a culture that is dying out,” said See. “In about 15 years it will be gone.”

After finishing her last novel, Tea Girl of Hummingbird Lane, about tea growers among China’s Akha minority, See focused her attention on Jeju. As her bestselling novels feature many stories of female friendship and sisterhood, the haenyeo’s matrifocal culture, in which women are the breadwinners, was part of the fascination.

“What is matrifocal,” said See. “How does it differ from matriarchal? What rights does it give women? To me, they have an incredible amount of independence for women of their generation.”

Given the difficulty of growing crops on a volcanic island, residents have long harvested food from the sea. For centuries, deep sea diving has been women’s work and that labor division influenced gender roles. Women risked their lives to feed their families, while men—considered unfit for the rigors of diving—stayed home, watched the children, and cooked meals. In a traditional haenyeo household, a boy’s birth was welcomed because he would ritually honor his ancestors, but a girl’s birth was celebrated because it meant the family would have food. The enduring prominence of shamanism on Jeju-do, with its worship of goddesses, also helped preserve the matrifocal culture.

“Korea is the most Confucian country in Asia,” said See. “Yet Jeju was different. It had that kind of conflict between serious patriarchy and these women who had some independence. I was fascinated by what that did to men and what kind of power the women had and how they used it. Of course, that’s changing. A lot of that culture has changed.”

Traditionally, the haenyeo began training at a young age. After demonstrating underwater skills, a young woman would become a member of a diving collective. Haenyeo learned to dive up to 30 meters deep and hold their breath for over three minutes without diving equipment. They also learned to avoid danger, to not suddenly reflexively inhale sea water, to be wary of jellyfish and sharks and not to let themselves get entangled underwater. One mistaken breath could be fatal, and it was said that a haenyeo entered the sea with a coffin on her back. Despite the danger, families needed to eat and women had few other options.

When Jeju’s girls first began to attend school, everything changed.

“In the late 1970s, Korea finally had education for girls,” said See. “People with money had been able to send girls to private school but suddenly all girls could go to elementary school and it was less expensive. Once all daughters could go to school, their mothers saved money to send them there. The first generation that got to go to college did become doctors, dentists, engineers, and worked in hotels. They had so many opportunities that their mothers and grandmothers didn’t have.”

Within a few decades, the numbers of haenyeo had dwindled dramatically.

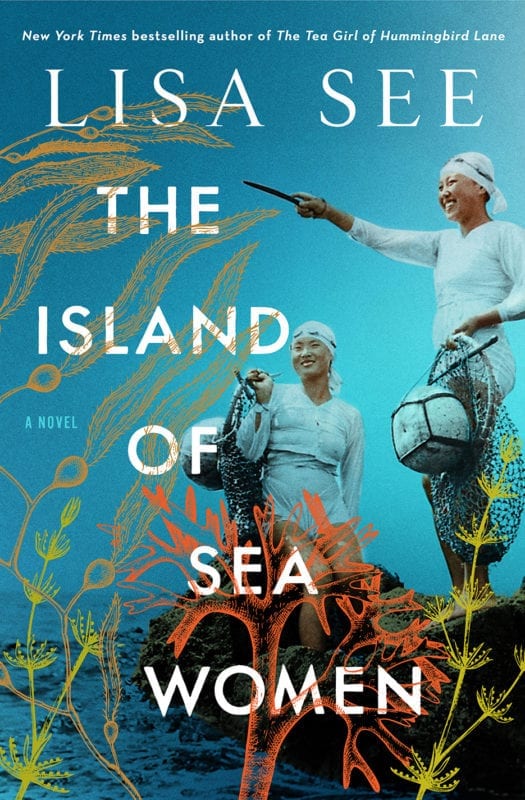

she met during her time in Jeju. [Photo: Lisa See]

See was not sure what time period to set the story in until she learned about the 4.3 Incident. Memories shared during interviews prompted the author to focus on the Japanese colonization of 1910 to 1945 and the time between April 1948 and May 1949, when a campaign to suppress a supposed communist insurgency resulted in military and police forces killing 10 percent of Jeju’s population. The 4.3 incident took place on April 3, 1948, when protesters attacked police stations and, in retaliation, tens of thousands of islanders were killed and hundreds of villages burned.

Making the massacres even more tragic was the edict that no one could talk about what happened. Mention of the massacres was suppressed for decades by threats of beatings, torture, and imprisonment. It was not until 2006, almost 60 years after the rebellion, that the government apologized for its role in the killings. For See’s subjects, talking about the incident provoked painful memories.

“When I was there the pain was palpable, especially in the more private interviews with older people who lived through it. Everyone was affected in some way. And they could not talk about it. For more than 50 years, if you talked about it you could go to jail. Your children could be punished. Your grandchildren could be punished.”

Although islanders remained in separate camps for a long time, eventually the island began to heal, and a Peace Park was created to honor those lost.

“There was one village that divided into two, one village where there were more victims and the other village where people in the police or army or who were Japanese collaborators lived. As part of this island’s healing and the process of forgiveness, the two villages decided to reunite back under their original name. The heart of my book is this idea of forgiveness.”

See personifies her story of forgiveness in the characters of two haenyeo, who grow up as close as sisters. In The Island of Sea Women, readers meet Young Sook, a fledgling haenyeo. She and her mother befriend Mi Ja, the motherless daughter of a Japanese collaborator, taking her into their diving collective. Although the women’s friendship lasts for years, they are forced into different sides of a heart-wrenching conflict, each powerless to stop the unfolding events.

The story of Young Sook and Mi Ja was shaped by conversations See had with the haenyeo she met during her time in Jeju.

To set up interviews, See enlisted the help of three women who knew their way around the island: Dr. Anne Hilty, Korean-American writer Brenda Paik Sunoo, and academic Jeni Hahn. Hilty is an expert on Jeju’s geography, shamans, goddesses and the 4.3 incident. She has written about the haenyeo for The Jeju Weekly and National Geographic Traveller and is the author of Jeju Haenyeo: Stewards of the Sea.

Brenda Paik Sunoo, a Jeju resident, is the author of Moon Tides: Jeju Grannies of the Sea. Jenie Hahn translated several oral histories for See and served as a reference for the stories of the island’s culture and goddesses. Through these women, See received introductions to haenyeo, shamans, and academics, as well as experts at the island’s Haenyeo Museum. While some interviews were arranged in advance, See also encountered haenyeo walking along the beach and was often spontaneously invited by museum staff to accompany them on visits.

“Some interviews happened when they said, ‘I know someone, let’s just walk over there.’ And then I’d unexpectedly be sitting on the floor in someone’s house drinking citrus tea. Everyone was so gracious in wanting to talk about their lives.”

The vitality of one 91-year-old haenyeo surprised her.

“The woman was so tiny, 85 pounds, and in her early 90s. You often meet people that age and their mind wanders, they get tired. After a while, we said we could come back on another day, but she said, no, have a cup of tea, and we talked for hours and hours. We were all worn out. She was not.”

That interview turned out to be a high point for See. The haenyeo’s daughter had accompanied her to the interview. On the drive back the daughter said her mother had shared stories during the interview that she’d never heard before.

“Most families don’t ask questions of those who are older,” said See. “Or they don’t ask the second question, the follow-up question that goes a little deeper. When she was translating, she was blown away hearing about her mother’s life.”

All of See’s previous novels focused on her Chinese-American heritage. The Tea Girl of Hummingbird Lane is set in a small village of tea growers, whose lives change dramatically as their tea becomes a valuable commodity. Snow Flower and the Secret Fan takes readers to 19th century China, when wives and daughters had bound feet and lived in seclusion. Gold Mountain tells the story of See’s great-great-grandfather arriving in America, prescribing herbal remedies to immigrant laborers who were treated little better than slaves. China Dolls is set in 1938 San Francisco when three young women from different backgrounds meet at the glamorous Forbidden City nightclub.

The Island of Sea Women was See’s first venture into writing about Korea, and, while she did have to brush up on some Korean history and culture, she didn’t see the research for this book as more complicated than previous books.

“When I’m writing about 19th century China I didn’t live through that time. I don’t know what it was like to have bound feet and live in total seclusion. When writing fiction you have to do the research and put yourself in their clothes and try to get it right. That’s true of all the stories I write. I want to do my best and get it right.”

It was important to portray the struggles and strength of the haenyeo during this period in history.

“All of us live in history and I feel it ’s a good thing for us to think about our own lives and what we would do in a similar situation. So many people around the world are living in situations over which they have little control.”

Before the haenyeo entered the sea, they would take part in a bonding ritual that fortified them for the possibility they might not return.

“The sense of fortitude and persistence, going forward, no matter what, is something very powerful about human beings, that desire to survive and thrive. We’re humans, so we go on.”

The Island of Sea Women will be published on March 5, and it’s Korean translation (by BOOKRECIPE) is in the works, but not yet announced.